Recent Articles

Home » Posts filed under Wellcome Collection

Showing posts with label Wellcome Collection. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Wellcome Collection. Show all posts

Friday, May 6, 2016

Fetish skulls! Wax guts! Dead kittens! Attending a Morbid Anatomy lecture feels like re-uniting with an old friend. It's been nearly four years since Seize the Day and judging by the fact that this event sold out in a matter of minutes, death appears to be extremely en vogue.

Morbid Anatomy are at the forefront of contemporary death, with Joanna Ebenstein's excellent blog having developed into the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York City. Their mission statement is "to excavate the intersections of the history of art and medicine, death and culture" and to that end they presented four very different but equally fascinating lectures.

First up was Chiara Ambrosio, who transported us to an obscure cave on the wrong side of the tracks in Naples. This is the Fontanelle cemetery, where the chaotically scattered bones of Neapolitans lie, many dating from the great plagues that periodically decimate the city's poor. Over the years, a cult has arisen around these bones, its devotees constructing miniature 'homes' for skulls and seeking practical and spiritual advice from them in their dreams. This personal hotline to the afterlife threatens the monopoly of the Catholic Church, who declared that the devotees had "degenerated into fetishism" and ordered that the practice end. Which it did. At least the devotees said they'd stopped...

|

| Skulls in Fontanelle Cemetery |

Secret death cults in obscure Neapolitan caves are (by my standards at least) completely infused with romantic adventure. Accentuating this is Ambrosio's lyrical and poetic analysis of the phenomenon, her lecture accompanied by live musical accompaniment. She created a woozy, dreamlike atmosphere - beginning with the surface geography of the city and subsequently burrowing deeply into the psychology of its inhabitants.

Next was Kate Forde's retrospective on the Wellcome Collection's 2009 exhibition Exquisite Bodies, which showcased wax anatomical models from the 19th century. These 'anatomical venuses' awkwardly straddle dispassionate medical education and quasi-religious eroticism. Forde gave us a whistle-stop tour through the history of wax anatomical models in London; explaining how they were first considered an unambiguous public good but soon fell victim to pearl-clutching Victorian moralists.

|

| Anatomical Venus by Susini and Ferrini |

Throughout the talk I was mentally filing away things to research in depth later; Dr Kahn's wildly popular anatomy museum in Leicester Square; the delights of the Roca Collection and the classically beautiful, impossibly detailed wonders of Susini and Ferrini. Underneath all this lies a weird dichotomy between the surgery and the freakshow - the wax figures attracting attention as much for their sensuousness as their instructive anatomical detail. I hesitate to plumb the psychological dark spaces that fuel their popularity - what does is say about men who're attracted to a passive feminine body that invites you to strip her down to her womb?

This was swiftly followed by the personable Ross MacFarlane, with Death and Dr Buchan. Dr Buchan was a medical celebrity of the 18th century, feted for his globally popular Domestic medicine, a layperson's guide to treated common maladies. MacFarlane examined the impact of this book through Robert Burns' Death and Doctor Hornbook, in which a man comes across a despondent Death, worried that his services are longer required due to the activities of the titular Doctor. Yet Hornbook isn't some medical wunderkind - his self-taught home treatments are simply killing off far more people than Death ever could.

How much should the public know about medical science? This knowledge used to be the preserve of professionals; who perhaps assumed the general populace was too stupid to understand medicine or (more likely) was afraid that wide dissemination would weaken their businesses. Authors like Buchan broadened access to this knowledge, yet, as Pope famously said, "a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing".

While there are numerous minor problems that people can treat themselves, there's much that probably should stay in the realms of professionals. One only has to look at the rise in internet self-diagnosis/treatment or the alternative medicine industry to see what can happen when people think they know better than a trained professional.

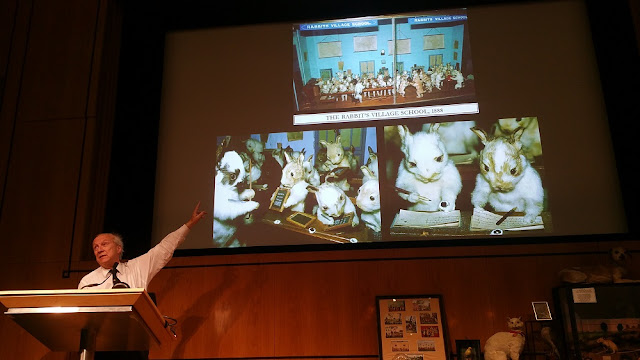

Finally we get to Dr Pat Morris, former Senior Lecturer in Zoology at the University of London and authority on taxidermy. The subject was the taxidermy of Walter Potter, clearly a passion project for Morris. The origin is a visit to his small museum "when I was in short trousers", where he was confronted by his striking anthropomorphic dioramas, the most famous being The Death and Burial of Cock Robin. I can see why he's such a fan - I got to see them (courtesy of Dr Morris) at 2013's The Museum of Everything) and they're just the right cocktail of weird and cool.

With the aid of examples he's brought with him, he gives us a brief biography of Potter. This ties into a wider ruminance on the popularity of taxidermy in Britain. A stuffed bird or family pet would have been an everyday sight in a Victorian household, but postwar squeamishness caused a gradual loss in popularity. Fortunately, taxidermy is on the rise again: chic workshops where you can 'stuff your own mouse' booked up for months in advance.

Dr Morris regards these johnny-come-latelys with a faint sniffiness, pointing out that the same kind of contemporary artwork that's now selling for big bucks was being done by his co-workers ten years ago - to little acclaim. Still, he must be pleased that the Potter works he's saved are being appreciated anew and judging by the crowds that gathered at the front of the lecture hall appreciated quite passionately. I love them: a three dimensional, powerfully physical manifestation of creatures, scenes and personalities long dead.

Once again Morbid Anatomy proves to be very much my kind of event. I look forward to the next thing they have coming up. One day, one glorious day I will visit their New York museum.

|

| Death and Doctor Hornbook |

How much should the public know about medical science? This knowledge used to be the preserve of professionals; who perhaps assumed the general populace was too stupid to understand medicine or (more likely) was afraid that wide dissemination would weaken their businesses. Authors like Buchan broadened access to this knowledge, yet, as Pope famously said, "a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing".

While there are numerous minor problems that people can treat themselves, there's much that probably should stay in the realms of professionals. One only has to look at the rise in internet self-diagnosis/treatment or the alternative medicine industry to see what can happen when people think they know better than a trained professional.

Finally we get to Dr Pat Morris, former Senior Lecturer in Zoology at the University of London and authority on taxidermy. The subject was the taxidermy of Walter Potter, clearly a passion project for Morris. The origin is a visit to his small museum "when I was in short trousers", where he was confronted by his striking anthropomorphic dioramas, the most famous being The Death and Burial of Cock Robin. I can see why he's such a fan - I got to see them (courtesy of Dr Morris) at 2013's The Museum of Everything) and they're just the right cocktail of weird and cool.

With the aid of examples he's brought with him, he gives us a brief biography of Potter. This ties into a wider ruminance on the popularity of taxidermy in Britain. A stuffed bird or family pet would have been an everyday sight in a Victorian household, but postwar squeamishness caused a gradual loss in popularity. Fortunately, taxidermy is on the rise again: chic workshops where you can 'stuff your own mouse' booked up for months in advance.

|

| The Death and Burial of Cock Robin |

Once again Morbid Anatomy proves to be very much my kind of event. I look forward to the next thing they have coming up. One day, one glorious day I will visit their New York museum.

Thursday, March 26, 2015

A successful historian must play psychoanalyst to their period. Entire societies are gently laid on the couch, their ambitions, paranoias, pride and history intelligently probed in an effort to get at what made them tick. You could look at what they say about themselves, but this strays into the realm of propaganda, neither individual nor civilisation wants to look like a chump.

You can approach this understanding of the past through many prisms, each refracting the past in their own way. Professor Andrew Scull has chosen the processes and understandings of mental illness: the understanding of cause, processes of diagnosis and treatment shedding light into the minds of our ancestors.

This interrogation is the subject of the 2015 Roy Porter lecture, hosted by the wonderful people at the Wellcome Collection. Prof. Scull, a former colleague of Porter, is Distinguished Professor if Sociology and Science Studies at the University of California, San Diego. His new book, Madness in Civilisation: The Cultural History of Insanity has just been released and provides the raw material for this lecture, which zeroes in on the nascent science of mental illness in the 1800s.

|

| George Cheyne |

Our introduction to this world is the pioneering work of physician George Cheyne. His publication, The English Malady; or, A Treatise of Nervous Diseases of All Kinds, as Spleen, Vapours, Lowness of Spirits, Hypochondriacal and Hysterical Distempers (1733) was a huge influence on popular conceptions of mental illness and depression. That title, with the English laying proud claim to mental disorders, initially feels a touch odd. Why would an proud, patriotic nation hurry to 'own' these conditions?

As a point of comparison, Prof Scull explains the shifting colloquial names for syphilis, which in England, was called 'The French Disease', in France 'The Italian disease', in Italy 'The Neapolitan disease' and so on, with the Turks throwing their hands up and simply calling it 'The Christian disease'. These pejorative names are reflections of nationalistic spite: after all, nobody really wants to be 'the syphilis country'.

|

| George Durer's Syphilitic Man |

What this reveals is that far from being a negative, 'nervous disorders' were proudly incorporated into the English psyche as a point of patriotic pride. The explanation for why is based around comparing 'primitive' and 'modern' man. The primitive has their mind occupied with acts of survival, a daily life and death struggle for food and shelter. Whereas the modern man, with his refined sensibilities, sharpened mind and rarefied talents, is akin to a precision-tooled piece of machinery - with many more components able to fail. Or, as Cheyne put it:

"those of the liveliest and quickest natural Parts...whose Genius is most keen and penetrating were most prone to such disorders. Fools, weak or stupid Persons, heavy and dull Souls, are seldom troubled with Vapours or Lowness of Spirits." CHEYNE (GEORGE) The Natural Method of cureing the Diseases of the Body, and the Disorders of the Mind depending on the Body.

So, the more Britain succeeded economically, scientifically and culturally, the more 'nervous disorders' we should expect to see - with mental illness an unexpected herald of social success.

This period of history, with luminaries like Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke, Edmund Halley and Christopher Wren et al defining the boundaries of the universe and identifying hitherto unknown invisible forces like electricity, gravity and magnetism must have been an astonishing time to live through. Finally the nuts and bolts of the universe were being revealed, the role of God gradually moving towards to absent caretaker rather than a being that intervenes in the lives of men.

Anything must have seemed possible, an outlook that gave rise to the success of one Franz Mesmer. He invented the concept of 'animal magnetism'; that energetic transference takes place between all objects, animate and inanimate. By manipulating this process he claimed to be able to cure nervous illnesses. Word soon got around, and before long crowds rich and poor were clamouring for a taste of mesmeric therapy.

|

| A mesmerist using his 'magic finger' to cure a comely woman. |

It was all bunkum of course, Prof Scull inferring that a decent portion of his success came from providing erotic experiences for buttoned down society women. With scandal constantly nipping at his heels, Mesmer hopped between European cities, eventually coming a cropper at the hands of a scientific dream team that included Antoine Lavoisier, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, Jean Sylvain Bailly, and Benjamin Franklin. They conducted tests, concluding 'biomagnetic fluids' to be a load of cobblers. Mesmer soon vanished into obscurity, the last 15 years of his life large unknown.

Though firmly discredited, his therapies acted as a seed in treated conditions of the mind. Mesmer's animal magnetism therapies evolved into hypnosis therapy (from which we get the word 'mesmerism'). We later learn that Sigmund Freud began his therapeutic career as a hypnotist, the interaction of patient and clinician eventually formalising into psychoanalysis.

It's here that Prof Scull links the behaviour of the past to the present. His examples outline the broad strokes of the 18th century 'personality': nationalism, scientific progress and a belief in progress. Mesmer's popularity inevitably leads the mind toward modern pseudo-scientific therapies, arguably more popular now than they've ever been. Similarly, the ownership of mental disorders feeds into identity politics: in an increasingly homogenous world everyone wants to stand out, with internet self-diagnosis leading to the rise of 'disease/allergy/mental illness as fad'.

What will future historians think of us when they examine these trends? What rationale can be given for masses of people running to alternative therapies when faced with the myriad miracles of modern medicine? Why are increasingly large amounts of people desperate to find 'their' disorder?

Perhaps it's only with the hindsight of history that the answers can really be theorised. Nonetheless, Prof Scull's lecture leads us down fascinating intellectual paths, subtly nudging us towards applying historical analysis to modern trends. It was a real treat watching him speak, I'll have to get hold of his book.

Prof Scull's book, Madness in Civilisation: The Cultural History of Insanity is available here.

Monday, December 1, 2014

With its dull grey decor and formal atmosphere The Institute of Sexology is the epitome of 'just-the-facts-ma'am' seriousness. This soberness makes for an interesting contrast with the subject matter; galleries of knobs, tits and fannies in various states of erotic arousal, most of them owned by people wrapped up in psycho-sexual knots.

What the Wellcome Collection wants to emphasise is that sexology is a serious-minded, rigorous and important academic discipline. They're absolutely right, but it's difficult to suppress a childish giggle when you're confronted by a Greco-Roman winged boner. It's this tug of war between high-minded academia and puerile sniggering that runs right through this exhibition, the snooty air almost daring you to make some immature joke.

+(c)+Wellcome+Library,+London.jpg) |

| Masked man in pink tutu, from collection of Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840-1902). |

Covering just two and a bit rooms, the exhibition spans 150 years of sexological research. We begin with Victorian pioneers who stuck their toes into what they considered perversion, inversion and moral decay. Perhaps the best example of this early work is Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing's textbook Psychopathia Sexualis (a potentially truly great band name). This work, famous for popularising the terms masochism and sadism, is one of the first to catalogue fetishes and the spectrum of eroticism. Krafft-Ebbing feared his work could be used for cheap titillation, so gave it a scientific sounding title and wrote parts in Latin, efforts that are neatly mirrored in this exhibitions efforts to remain respectable and educational.

From here we spiral up through the late Victorian and arrive in 'The Consulting Room', where we see the duelling philosophies of Sigmund Freud and Marie Stopes. There's a simulated version of Freud's desk, populated by his totemic figurines and, my favourite, a bronze porcupine. As far as analogies go I've always enjoyed 'The Porcupine's Dilemma'; to keep warm they must huddle together, but in doing so they risk jabbed by each other's spines - a neat summary of interpersonal relationships. Freud's "the talking cure", involved solving a patient's sexual issues through a comprehensive mapping of their pasts, dreams and mind.

+Wellcome+Library,+London.jpg) |

| Marie Stopes birth control clinic in caravan, with nurse, late 1920s. |

This couldn't be further from his contemporary Marie Stopes, who indignantly warned her patients to not “think about your subconscious mind ...as all the filthiness of this psychoanalysis does unspeakable harm.” Stopes is a fascinating character; described as an "feminist, eugenicist and paleobotanist". Her mission in life was to lower birthrate among "undesirables" (i.e. the poor), which is, well, a bit disturbing. But, from the worrying soil of class snobbery grew green shoots of contraception and unprudish sex advice for couples.

It's characters like Stopes that shine through in this exhibition; the idea of a fossil-hunting, feminist, eugenicist fastidiously recording her arousal levels appeals to me on some basic level. Just past Stopes is a similarly magnificent project; a catalogue of all the men that a New York based artist, Carolee Schneemann, slept with over the course of a few years. The men are rated for their skill, masochism, tenderness and the sounds they made when they came. This reducing of something as chaotic, fuzzy and sticky as sex into cold hard data is somehow intrinsically absurd: can you bake love into a pie chart?

+The+Kinsey+Institute.jpg) |

| Alfred Kinsey interviewing a woman. |

The pinnacle of this was the exhaustive research undertaken by Dr Alfred Kinsey. After a long period categorising millions of wasps (he eventually concluded that no two are exactly alike) he moved onto sex. You can leaf through Kinsey's questionnaire and quickly understand just how he got thousands upon thousands of people to reveal the most personal details of their sex lives. His method was like the famous example of boiling a frog i.e. to gradually raise the temperature so it cooks alive. One moment a Kinsey interviewee is talking about their first memory of a birthday, the next they're being asked whether they're had a dildo jammed up their arse (and if so what colour, size and make it was).

This compartmentalisation of sexuality into strictly defined categories is fascinating from a scientific point of view, but at some point you've got to ask: where's the love? I had hoped this would come from the exploration into the work of Wilhelm Reich. He's one of my favourite loopy countercultural figures, becoming convinced in the 1940s that he has discovered a cosmic source of energy; orgone. Famously summarised as a mystical sexual energy, Reich built 'orgone accumulators'. Here you get to sit in one.

I'd wanted to sit inside an orgone accumulator for years - particularly after watching the ace film W.R. Mysteries of the Organism. Now the time finally came and, to be honest it was an anticlimax. The accumulator is a foam-covered plywood box lined inside with sheet metal, the design supposedly able to draw down this aetheric energy and concentrate it in my body. Instead it felt much like being sat in a photobooth at a train station. Oh well, maybe this stolid environment isn't a natural place for funky sex magic.

It'd be a lie to say that The Institute of Sexology isn't interesting. It's carefully and rigorously designed to pack as much key information into this small gallery. That said it's a cold and distant exhibition, one that all but demands you surrender your emotions at the door. This absence of playfulness works against the eccentric aspects of characters like Reich, Stopes and Kinsey that populate the display cabinets.

It all adds up to an interesting but not particularly passionate (and certainly not sexy) experience. But I suspect that's exactly what they were shooting for.

The Institute of Sexology is at the Wellcome Collection until 20 September 2015. Free entry.

Monday, November 5, 2012

I seem to spend an inordinate amount of time on this blog talking dusty old bones or exploring gooey innards. I don't consider myself a particularly morbid person, but there does seem to be a lot of death related stuff about at the moment in London. But hey, you don't have to crack open the eyeliner and put on an ankh necklace to find this stuff both scientifically and philosophically interesting. The event at the Wellcome Collection on Friday night aimed to examine the myriad different facets of death, and what it can mean to us personally and culturally. Rather than being Halloween related, it coincided with Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, which lent proceedings an upbeat atmosphere rather than creaky old Victorian theatrics. There were a load of activities going on around the gallery itself: dance lessons, arts and crafts and music was provided by the Silk Street Jazz band who played a selection of jazz funeral tunes.

But I didn't have too much time to look around. I made a beeline straight for the lecture theatre to hear the three speakers: Joanna Ebenstein, David Spiegelhalter and Frank Swain. All were talking about death and all approached the same subject from very different directions.

|

| Joanna Ebenstein |

Joanna Ebenstein runs the blog 'Morbid Anatomy: Surveying the Interstices of Art and Medicine, Death and Culture'. She begins by broadly examining the different ways in which modern cultures treat death. In the US, death imagery is largely relegated to the realm of goth/metal bands or horror films. Death is something to kept under the rug, regarded as the preserve of the morbid teenager, a concept not discussed in polite company. The theme of this evening is the Day of the Dead, so she invites us to examine the differences between Mexican and US culture. There is a much higher degree of willingness to engage directly with death in Mexico, as shown during Dias de los Muerte, which has its origins deep in pre-Christian Aztec traditions. Nowadays though, a few centuries of Christian cultural hegenomy has resulted in the two imageries becoming intertwined.

|

| This is what happens when millennia old religions crash headlong into each other. Pretty rad. |

Reaching back into the past, Ebenstein details her passion for 'medical venuses'. These are realistic wax models of classically beautiful women with detailed innards that curious visitors could remove to try and understand anatomical architecture. Rather than the piles of coiled guts tumbling from their bellies, it's their faces that grab my attention. They're frozen in some kind of ecstasy, be it religious or sexual. This feels like a kind of logical endpoint tomale exploitation of female vulnerability, a literal objectification of every part of the body, from the skin down to the depths of their entrails. We see pictures of men with big bushy moustaches wearing top hats, their hands plunged deep inside the female body. To our eyes in the present they're powerfully charged with political, historic and psychological significance.

|

| A medical venus |

|

| Foetal skeleton tableaux |

At the same time the Grand Guignol was approaching the height of its popularity, a precursor of the modern slasher picture. One common theme I picked up from this lecture was that every culture seems to need some kind of release valve for their death instinct. Whether it be through 'high or low' culture there is a universal human urge to occasionally wallow in the waters of the Styx. In this light, the Grand Guignol is a precursor to today's torture porn horror films. So, far from being just another example of Western society undergoing to a prolonged slide into depravity, films like the 'Saw' series (total worldwide gross $873,000,000) are merely the modern equivalent of something that's always been with us, and something that's always been popular.

That's why I agree with Ebenstein when she criticises those who would define her as unhealthily morbid. I think it's far more interesting to try and understand what our irresistible compulsion to explore this subject says about the psychology of humanity, and how we bear the burden of being the only animal with the foresight to see the Grim Reaper somewhere up the road ahead of us, tapping his scythe impatiently.

|

| Prof David Spiegelhalter |

Just how far ahead of us the Grim Reaper is fuels the subject of our next lecture, by Prof David Spiegelhalter. He's the Wilton Professor for the Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge. Being in charge of the public's understanding of what is risky and what isn't seems like a bit of a Sisyphean task, people in general are notoriously bad at calculating what is risky. Being told their perceptions of relative danger are faulty can produce some powerful political and social reactions. At one end of the scale, telling people that statistically speaking they're far safer travelling by air than by car is generally a comfort to those with a fear of flying, whereas telling people that riding a horse is more dangerous than taking ecstasy will provoke widespread derision.

To begin with we're presented with data showing how life expectancy has improved drastically over the last century or so. With leaps in medical science and the implementation of the National Health Service we're healthier than we've ever been and consequently living longer. The trend is such that, as Prof. Spiegelhalter explains, that for every year we live, our life expectancy increases by about 3 months. This obviously can't go on forever, but things are going to get very interesting when we start pushing up against just how old a person can be. It strikes me that humanity at the moment is a bit like King Canute ordering the tide back, but perversely we're actually succeeding.

How does a person begin to correctly quantify the amount of risk they subject themselves to? The answer is a fascinating statistical construct known as the micromort. A micromort is a unit that measures a one in a million chance of dying from any given activity. This allows us to calculate, using statistical data from various sources, how risky things are. A one in a million chance is a very hard thing for the human mind to comprehend. Every week about 32 million people play the lottery, with a vanishingly small chance of a particular individual winning the jackpot. But conversely this jackpot gets won pretty much every week by somebody. A one in a million chance is therefore vanishingly rare and also an everyday occurrence. Without wishing to dip my toes too far into the extremely murky waters of evolutionary psychology, I just don't think humans are built to logically process probabilities like these.

This inability to grasp in real terms how dangerous the world around us makes units like the micromort a useful construction. It allows us to directly compare the relative danger of methods of travel, as shown in the graph below:

As you can see, by car is statistically the safest way to travel. You can get 250 miles on one micromort, whereas you'll use up a whole one in only 6 miles of travel on a motorbike, or 11 miles walking. The micromort makes for some eye-catching and exciting graphs, and is good at allowing us to work out one-time dangerous events like skydiving, but later Prof. Spiegelhalter presents us with what I consider to be a more immediate explanatory tool: the microlife.

A microlife equals 30 minutes of life expectency, and is a way of measuring the impact of long term habits on the human body. For example, smoking two cigarettes might cost 1 microlife, or drinking 7 units of alcohol. A 30 minute span of time is something we can easily perceive and imagine, and the notion of just a little bit more sand trickling through the hourglass of our lives is arresting. Thinking too hard about microlifes and how many you spend on various activities is the kind of thing that might drive a person insane, imagine someone sitting down with a calculator and planning your day based around using up the minimum amount of time.

Both of these units, micromorts and microlives are obviously not particularly hard science. ; it's impossible to test these things as we can never know someone's exact life expectancy. What they are fantastically useful as is thought experiments, a way of trying to look at the world through a different lens, to try and peer through the fog of human bias and understand exactly what calamity awaits us at every turn. This was a fascinating lecture, and Prof. Spiegelhalter is a brilliantly charismatic lecturer. I thoroughly enjoyed every part of it.

|

| Frank Swain |

Last on the bill was Frank Swain, author of the forthcoming book 'How to Make a Zombie'. He gave us a tour through the history of human reanimation, a tale that takes in some very odd individuals.

We began with the tale of Anne Greene. She was a domestic servant who in 1650 was seduced by her master's grandson and subsequently gave birth to his child. The baby was stillborn and Anne was unjustly sentenced to death by hanging for infanticide. Execution by hanging at the time was a somewhat sadistic affair, the ropes were so short that death was invariably by strangulation rather than by the neck snapping. So Anne asked her friends to pull at her feet and beat her hanging body severely so as to ensure that she was really dead. What else are friends for?

|

| The execution of Anne Greene |

Soon she was cut down, but someone detected a faint pulse of life still within her. They gradually revived Anne, massaging her limbs and eventually having another woman lie on top of her in bed to keep her warm. She made a full recovery. This left the justice system in a bit of a quandary. The sentence had been carried out, and apparently Anne had indeed died. Should they hang her again? Eventually it was decided that her survival was due to the direct intervention of God. Anne was pardoned, and apparently rode out of town on top of the coffin she was due to be buried in.

It's a great story and one that shows an early example of people being revived after an apparent death using techniques (massage, heating) that we still use in some form to this day.

When examining the history of reviving people from the brink of permanent death it's important to realise that the dividing line between the two is more tricky to pin down than you might assume. Being mistakenly pronounced dead and buried alive (taphophobia) was a huge fear in the 18th and 19th centuries. Inventors struggled to solve the problem by creating 'safety coffins' equipped with breathing tubes, bells and glass lids for observation.

This growing blurriness of the dividing line between the living and the dead was further confused by the trend for 'galvanism' in the late 19th century. The properties of electricity weren't clearly understood by the general public and travelling quack scientists electrocuting corpses and causing them to twitch and blink were so prevalent that some local governments banned the practice. All of this added up to a feeling that science might be on the verge of conquering death once and for all.

This passion for galvanism reached a grisly zenith in the work of Karl August Weinhold, who Swain describes as 'the most villainous scientist he encountered'. This is a man who would decapitate live kittens and insert batteries into the headless body to try and make it dance about. This was very effectively demonstrated by Swain picking a volunteer from the audience and making her cut the head from a plush toy, before inserting batteries inside. It sounds a bit cheesy, but hell, it's a memorable and entertaining teaching method. This practice fell out of fashion as it quickly became apparent that galvanism was more of a weird sideshow than any practical way of raising the dead. And also because any science that involves cutting the heads off live kittens is inevitably going to have an image problem.

The next big steps were made in Russia. Swain shows us what he describes as "the best opening sentence of a science article ever":

"Vague reports have been reaching the U.S. that Russian scientists have revivified corpses" - Time Magazine 1929

It is admittedly quite attention grabbing, like something you'd see at the start of some zombie film. Russian scientists were indeed engaged in some pretty weird sounding experiments, most notably Dr. Sergei Bryukhonenko who was busy keeping severed dog's heads alive on a heart and lung machine of his own design. You can watch a video of this process here but I should warn you it is weird as hell.

After this we heard the tale of Dr Robert Cornish, a child prodigy biologist who received his doctorate in 1924 at the young age of 22. He decided to devote his life to the task of raising the dead, and one can't fault him for ambition at least. He determined that the problem of death was primarily that the blood wasn't flowing around the body, so Cornish constructed a kind of macabre see-saw on which he'd strap the corpse and violently tilt it up and down to force the blood around the body. After a few failures he decided that heat was needed too, but in applying heating pads only managed to partially cook the body. This was amply demonstrated by more volunteers from the audience (not the cooking part though). Back to the drawing board for Dr. Cornish.

In the history of revivification, it seems that dogs frequently get the short end of the stick, and Cornish began working on a series of dogs, all of which were optimistically named 'Lazarus'. Amazingly he DID manage to revive some of these dogs, but they appear severely brain damaged, blind and staggering about in a state of utter confusion. Creating a load of brain-damaged zombie dogs isn't a good image for any establishment of learning, and the University of California kicked him out. But undaunted he carried on his experiments in his garden shed! Needless to say his neighbours weren't best pleased, apparently being faintly terrified by strange fumes leaking from his property and a preponderance of half dead dogs lying around the property in various states of consciousness.

15 years later he'd become confident enough in his techniques to try and find a human specimen. His first attempt was with Thomas McMonigle, a murderer facing the gas chamber who was quite enthused about being returned back to life after his 'execution'. This, alas, was not to be. It proved impossible for Dr Cornish to have access to the body in time, "unless he wanted to sit in the gas chamber with him". I can understand the prison's point of view here, it's just not good PR to let people revive executed prisoners and maybe create zombified murderers. Anyway, what if he did succeed? Would they have to free him? Dr Cornish then left the prison, as did McMonigle, albeit more horizontally.

His last resort was to put an advert in the classifieds asking for a volunteer to be killed and revived in the name of science. Apparently he got a surprising amount of volunteers but never went through with the experiment. At this he got apparently bored of cocking a snook at death and decided to focus on his new passion, manufacturing and selling toothpaste. At which point his biography becomes far less interesting.

Many of these scientists sound like crackpots who have lost touch with all morality. Men with delusions of grandeur who want to control the forces of life and death at their fingertips. But, what we have to remember is that this branch of science has had its successes. Peter Safar, a pioneer in developing cardiopulmonary resuscitation professed his desire to "save the hearts and brains of those too young to die". Current promising developments in medical science involve the inducement of a 'controlled death state'. This involves draining the body of blood and drastically lowering the temperature, resulting in a kind of suspended animation where the brain's oxygen requirements are lessened dramatically. How long could a person be kept in this arrested condition, hovering between life and death?

Frank Swain is a fantastic lecturer, and is as knowledgeable as he is personable. All of the speakers at this conference were fascinating in their own ways, and I'm extremely pleased I attended. I know I seem to go to a lot of quite macabre events, but to be honest they're usually packed with the most interesting and fun people, and the most bizarrely compelling subjects. Death is one of the universal human experiences, yet perversely the only one we cannot experience directly without actually dying. I learned a lot tonight, and it felt right on Dias de los Muerte to raise a glass to the Grim Reaper. "To death!".

(If there's any factual errors here please let me know in the comments!)

(If there's any factual errors here please let me know in the comments!)

Monday, July 30, 2012

Very soon a momentous event in sporting history is about to take place. At the London Olympics, double amputee Oscar Pistorius will compete in the able-bodied 400m and 4x400m relay races. If he wins these events, something will change forever in athletics - a man relying on an external prosthesis, his 'blades', will have beaten the able-bodied athletes on a world stage. The notion of a physically augmented athlete being the most efficient and quickest contender will take firm hold, inevitably raising a number of ethical arguments about the relationship between the human body and technology.

|

| Oscar Pistorius competing with able-bodied athletes. |

It all sounds like cutting edge scientific debate - a conversation that previously would have been relegated to science fiction - but the Wellcome Collection's new 'Superhuman' exhibition outlines the long history of how men and women have replaced or extended their bodies capabilities and senses, as well trying to explore where we may be heading.

The first exhibit we encounter in the exhibition is a small statue of Icarus dating from ancient Greece. This is not exactly a cheery start to the exhibition, but it does seem appropriate. The notion of a millennia old story about the dangers of relying too much on technology shows us that these are issues that humanity has grappled with in some form or another for millennia.

|

| Icarus - 1st-3rd century CE, bronze |

One of the things that the exhibition is keen for us to understand is that human augmentation and prosthesis can take many forms. It's not all robot limbs and glowing red eyes - even something as innocuous as a pair of spectacles or a watch can be considered an augmentation. In the first display case we see items as disparate as a pair of Vivienne Westwood shoes, an iPhone and a blister pack of Viagra. We take many items like this for granted, but in a very real sense they can respectively be considered as augmenting beauty, memory and sexuality - three pretty essential components for humanity.

|

| Viagra (sildenafil citrate) |

Near this is another demonstration of a socially acceptable form of human modification - plastic surgery. In 'Cut Through the Line' a short film by Venezuelan artist Regina José Galindo, we see the artist standing naked (link NWS), with a plastic surgeon drawing marker pen lines across her body to show the changes he would make to her body. The loops and lines he draws across her look beautiful and faintly primal - as if she's being prepared for sacrifice. It's only when you remember that these lines of ink are guides for the scalpel to cut along that you understand the true import. The impact of the film, and the message it sends are quite clear. Galindo clearly has nothing wrong with her physically, yet to judgmental eyes there will always be a nip or a tuck somewhere that'll somehow bring her closer to an imagined universal standard of beauty. Her passivity as she stands naked with bystanders surrounding her, some filming her seems to both show her as a submissive canvas on which the plastic surgeon artist can realise his vision, while also showing her as an individual who is comfortable with her body as it is, and has no qualms about standing naked in front of people. This video outlines a compelling argument against the race for enhancement- would humanity be better off as a race of conventionally beautiful, technologically enhanced superpeople? If you can afford to recreate yourself like this, then where does individuality lie? And what about the people who're left behind?

|

| Pair of artificial legs for a child (red shoes), Roehampton, 1966 |

The next section of the exhibition that caught my attention was a display about the prosthetics developed in the 1960s to help victims of the Thalidomide tragedy. Pregnant women who'd taken a drug to prevent morning sickness found that their children were born with underdeveloped limbs, and well-meaning experts on prosthesis stepped in to offer their assistance on giving the children a 'normal' life. Displayed at the exhibition are a collection of these prostheses. Decoupled from their owners they look faintly disturbing, limbs constructed of leather, gas-cylinders powering movement with shoes incongruously placed on the feet. What this display highlights is that prostheses like these seem to be more for the benefit of everyone who has to interact with the person using them, rather than to help them. The people creating them doubtless had the best of motives, but the victims of the Thalidomide tragedy seemed to find it far easier to learn to cope with their limitations of their own limbs rather than learn to use these somewhat clumsy replacements. There is an interesting contrast between a video of a child delicately and neatly eating lunch in school using his foot to hold a spon, and of someone in a prosthetic 'suit' awkwardly trying to control arms constructed of hooks and springs. Manipulating one of these devices is described as like "being in a dream, where you can manipulate things, but can't feel them".

My perspective on this seems to be that doctors were in too much of a hurry to 'normalise' these children. The de facto position seems to have been that the conventional human body shape was what should be aimed for above all else. Their mistake was assuming that if a person looks normal, then the assumption must be that they feel normal - a position that conveniently allows able-bodied people to avoid dealing with the disabled person's condition. If someone can learn to utilise their bodies effectively in a way that works for them, irregardless of whether it might appear a little weird to onlookers, then that is something that should be aimed for.

|

| Thomas Hicks, Marathon Olympic Champion and his supporters at the marathon, St Louis Olympic Games, 1904 |

The next arena we examine is the world of sports. There are two areas to focus on - athletes using drugs to enhance performance, and physical aids. I was amazed to learn that in the early C20th, athletes would use strychnine to improve performance during marathons. The athlete, Thomas Hicks won the 1904 Olympic marathon after taking two doses of strychnine and brandy to ward off exhaustion. Not surprisingly, he collapsed and nearly died after crossing the finish line. A slightly more recent, and more disturbing example is the death of Tom Simpson in 1967. He was competing in the Tour de France on a bakingly hot day, and race rules at the time restricted athletes to about two litres of water per day. On a steep mountain climb he began weaving across the road before collapsing. While a medical team attempted to save his life he urged them to let him continue the race, shouting "Go on! Go on!". Three tubes of amphetamines were later found in his pocket - the drugs prevented Simpson from knowing he was dehydrated: he didn't realise he was dying.

The last minutes of Tom Simpson

Thankfully, deaths like Tom Simpson's are now extremely rare due to advances in anti-doping detection and an awareness of the dangers of doping. Yet athletes still seek to enhance their bodies with banned substances. One exhibit in this section is a fake penis called a 'Whizzinator' that allows athletes to fake urine tests. In a 2012 study by Leeds Metropolitan University it was discovered that athlete's attitudes towards banned substances was generally negative, although many of them understand the temptation. Athletes believe that 37% of their fellow athletes would use a drug if it was undetectable and guaranteed winning - 9% believe that their fellow athletes would use the drug even it led to guaranteed death within 5 years!

This intense desire to win lies at the heart of all professional athletes - arguably they wouldn't be professionals if they didn't have that burning desire for victory within them. It's easy to understand how they can come to rely on the crutch of a banned substance - especially in circumstances where a coach or instructor is advising the use something as safe, morally acceptable or undetectable.

|

| Pair of blue and yellow Nike waffle trainers, Nike 1977 |

The other, more uplifting side to human augmentation in athletics is physical prosthesis. This ranges from something as simple as running shoes. On display at the exhibition is an early C20th running shoe - it's a fearsome and uncomfortable looking thing made of hard leather and with a flat sole. Apparently athletes used to soak their feet in brine to toughen themselves up to wear it! So it was somewhat of a revolution when Bill Bowerman, coach of track sports at the University of Oregon developed a 'honeycomb' sole and new running shoe design - many of these innovations are still in evidence in running shoe design to this day.

The displays within the exhibitions are in rough chronological order, and as we get to the final rooms we begin to consider the future of human enhancement. There are a variety of theories, ranging from wearable computers, to internal organic implants, to gene therapy and even more science fiction applications of nanotechnology to the human body. One thing that is agreed is the future of humanity almost certainly lies with further augmentation of our bodies and senses.

There are two short films on display here that more than adequately demonstrate the dangers of this. The first tells us a fictional story of an injured US Marine who wins a contest to turn him into a superhero through prosthesis. The film takes the form of his video diary over a number of months - and we see his progression from a handsome and well-adjusted person to a monstrous and disorientated Frankenstein. Initially he starts out happy, enjoying the look of his new 'blade' legs, but as more and more is subtracted from him he begins to lose his humanity. There is one distressing sequence where his arm has been amputated and replaced with a prosthetic "that'll let me punch through walls", but as impressive as this might be, "it isn't so good at the small stuff" like fine motor manipulations. By the end, after he's had radical brain surgery and his eyes replaced by bleeding mechanics there is almost no trace of the excited and charming man at the start of the documentary - he's been replaced by a scarred and disorientated machine.

The other is a 'documentary' about the fictional condition Metalosis Meligna. The report shows us how people's metal implants have begun to take over their body. It's an extremely effective bit of body horror - reminding me of Shin'ya Tsukamoto's Tetsuo: the Iron Man (1989), with pieces of metal invading and taking over people's bodies. While Tetsuo treats this as surreal and frantic, this takes an almost perversely sober look at the 'metalosis' of sufferer's bodies. It's a nice allegory for our relationship with technology, and the dangers of immersion and reliance upon it.

|

| 'Metalosis Meligna' Floris Kaayk, 2006 |

The final piece of the exhibition is an autonomous wheelchair 'Psalms'. This piece was created by Donald Rodney, a sufferer of sickle-cell anaemia. He was too ill to attend his gallery openings, and a wheelchair was designed to take his place. The piece incorporates a neural network, and it wanders through the exhibition negotiating paths around us using various sensors affixed to it. Rodney died in 1998, and yet his wheelchair still roams the exhibition without him: a prosthesis making a lonely journey without its owner. This none too subtly points towards a possible future for humanity - that we will dissolve into or be replaced by what we have created to aid ourselves.

There is a theory popularised by futurists like Ray Kurzweil known as the 'singularity'. Here is the basic outline of how it may come about:

"Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make." - I.J. Good - 1965

This is sound thinking, but adherents commonly posit the singularity as a quasi-religious enlightenment of the human race. That it'll be a jump towards post-humanism, the end to all of our woes, that we will soon after become immortal, godlike digital intelligences. Thinking like this is one of my major issues with the notion of augmentation as inherently a good thing for the future of humanity. It seems that something like this would inevitably widen the gap between the haves and have nots - sure some people may jump forward, but at the expense of those left behind.

If a person is likely to experience a vast increase in awareness and intelligence due to an application of technology they are far more likely to be an extremely affluent person than, say a subsistence farmer in a Third World country. The gap between life at the lowest end of the poverty scale is wide enough already, and it is worrying to think of a world where the rich can afford to make themselves physically and mentally superior to us. How will these superhumans consider their interactions with us? The wealthy will have perfect photographic memories, be able to survive without sleep or run for miles - can we expect to be able to compete against them with our clumsy and imprecise organic brains and easily worn out and tiring bodies?

These are issues that we are beginning to have to face in the current day. Elderly people who are not connected to the internet risk losing out on essential interactions with their families - separated from them by an intimidating digital wall. As time progresses, we will find ourselves in their position, faced with a society plugged into each other in ways we might not be able to comprehend, or more likely, won't be able to afford.

There is a good argument that while there may be an initial stratification of society it will eventually even out. Look at mobile phones - once a trademark of wealthy financiers in the 1980s, and now a worldwide technology hugely popular and useful in African countries. The spread of the internet, possibly humanity's first global prosthesis is another way in which technology that was once the preserve of the wealthy eventually becomes accessible to all. I consider there be to be obvious silver linings to this cloud, but for a while it may be a pretty dark and forbidding cloud as we race to catch up with those who can afford to make themselves 'superhuman'.

|

| 'i-Limb ultra prosthetic hand', Touch Bionics |

This is a typically excellent, and highly thought provoking exhibition from the Wellcome Collection - a place which really should be more popular among London attractions. It's well laid out, gives us just the right amount of information and most importantly lets us come to our own conclusions about what we see. There is a wry sense of humour to some aspects of the exhibition, and some interestingly provocative choices in what to exhibit. I particularly liked the way that the information cards were pinned to the wall in a stretched, slightly surgical manner. My only criticism is that this is an exhibition that relies very heavily on video and the volume of them varies enormously. There are some that are so quietthat it is very hard to make out what is being said, while conversely a few are so loud that you can hear them across the entire exhibition. But in a summer where people are pushing their bodies to the limits of athleticism in the Olympics and Paralympics it's very timely and any visitors to this should find themselves watching some events in a different light. Highly recommended - and anyone attending should be sure to see the rest of the Wellcome Collections fascinating galleries.

If anyone visited this and wants to add their thoughts I'd be very interested to hear them, post in the comments below!

'Superhuman' is at the Wellcome Collection from the 19th of July until the 16th of October 2012.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Science+Museum,+London.jpg)