Recent Articles

Home » Posts filed under southwark playhouse

Showing posts with label southwark playhouse. Show all posts

Showing posts with label southwark playhouse. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

Of all Shakespeare's plays, Othello could be the most appropriate to be performed by puppets. After all, the titular character is nudged and prodded into a bloodthirsty rage by the manipulative Iago and how better to convey this than having him shove his hand up the character's jacksy and whirl him about the stage? This is Otelo, an abbreviated reworking of Othello by 'Chile's leading puppetry company', Viajeinmóvil and part of CASA Latin American Theatre Festival 2017.

Kicking off somewhere around the middle of the original play, Otelo boils the action down to its skeleton. Nicole Espinoza and Jaime Lorca play Emilia and Iago, who puppeteer the disembodied heads of Othello, Desdemona and Cassius. The two performers intertwine around one another, providing limbs and bodies for their characters, modulating their voices depending on which character they are and navigating a rotating bed set.

At its best, Otelo achieves a neat unity of performance, aesthetic and atmosphere. The disembodied head of Othello has exaggerated features which are accentuated by strong lighting - you could swear its dispassionate features change depending on the emotion of the scene - in the beginning, he is loving, but by the end, he is monstrous and broken - and the plastic visage remains the exactly the same. It's a fierce, pop-infected visual style and when combined with large sheets of primary coloured fabric proceedings take on the faint aura of Dario Argento's giallo.

Espinoza and Lorca are fantastic performers. There's no great sleight of hand here - they remain visible behind their puppets at all times. Yet rather than distracting us, their presence helps convey the emotions the puppets lack. Lorca in particular delivers up a believably frayed Iago riddled with guilt, corruption and ambition - sweatily realising he's in over his head as his plans come to fruition.

Otelo largely achieves its aims and is undoubtedly a singular piece of theatre. However, no matter how appropriate the puppetry translation is to the themes of the play and no matter how skilled the puppeteering, I couldn't help but feel as if there was something lost in translation from the original work. It turns out that there are limits to what can be achieved with mannequin heads, exemplified through the blank, almost sex-doll-like visage of Desdemona, whom Otelo literally objectifies and reduces to a figure of fun. That led to the frequent giggles the play received from the audience whenever the puppetry inched into melodrama. The show bills itself as 'darkly funny', but the moments of surreal silliness puncture the passion of Othello.

In addition, the play is in Spanish. That's not a criticism, but it is one more barrier between the audience (well, me at least) and the poetry of the play. Surtitles are projected above the stage, but frustratingly the person in charge seemed to be having an off night. They'd freeze for a couple of minutes then quickly cycle through the lines until we'd catch up, or fall out of sync with what the two actors were actually doing.

Otelo is an interesting and well-performed dramatic experiment, albeit one that I don't think is wholly successful. Oodles of care and effort have gone into this and Viajeinmóvil are undoubtedly incredibly talented puppeteers, but just I don't think the meat of Othello translates that well into a 75-minute puppet show.

Otelo is at Southwark Playhouse until September 30. Tickets here.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Typical isn't it? You wait around for a story about conjoined twins and then two come along at once. Just a couple of weeks ago at the London Film Festival I enjoyed Indivisible. The film followed conjoined twins Viola and Dasy, who spend their days being gawked at, singing musical numbers and debating whether they should be separated. Then comes Side Show, a musical about conjoined twins Violet and Daisy (Laura Pitt-Pulford & Louise Dearman), who spend their days being gawked at, singing musical numbers and... well you can probably see where this one is going.

The musical is a broad biography of Violet and Daisy Hilton, best known for their appearance in Tod Browning's 1932 classic Freaks. We follow them from exploitation in a travelling freakshow alongside bearded ladies, a half man/half woman and a three legged man. They live a miserable existence of sexual exploitation, humiliating performances and violent belt-based discipline. Life looks miserable as hell until vaudeville promoters Terry (Hayon Oakley) and Buddy (Dominic Hodson) arrive, liberating them and propelling them towards mainstream success. But though the costumes are glitzier and audiences snootier, have they really escaped the objectification of the freakshow?

From the first number Come Look at the Freaks we're tossed into an old-timey and, by contemporary standards, pretty offensive circus show. Messing with gender boundaries (the Bearded Lady (Lala Barlow) and the Half Man Half Woman (Kirstie Skivington) is shocking, deformity is something to be stared at and pitied and a black guy is reduced to dressing up in some ludicrous cannibal costume and beaten on stage. Perhaps even weirder is the Tattooed Girl (Agnes Pure), who seems incongruous in a circus setting (in 2016 she'd be more at home serving coffee in Shoreditch).

Director Hannah Chissick accentuates the circus atmosphere with thrust staging; allowing the performers to be seen from almost all angles. This all but invites us to gawp at the (simulated) on stage freaks. We look down our noses at the leeringly insensitive 1930s audiences, yet the show gently makes us feel like hypocrites. After all, we're the ones who've turned up to watch a high-kickin' rah-rah show about conjoined twins (though here their conjoinment appears to by a couple of safety pins).

This indictment eventually gets ladled on a bit too thickly. As the cast sings "come look at the freeeeaks" they put up mirrors in front of the audience as if to say 'ah, is it not you who are the real freaks?' Well, 'Lizard Man' and 'Dog Boy' it's an interesting hypothesis, but I still kinda think the freaks might be you guys. Mind you, not that there's anything wrong with being a freak.

That's the cheesiest moment in a show that bazookas its message at us with little subtlety or nuance. Ultimately, Side Show's moral lesson that people with disabilities are individuals in their own right rather than curiosities to be stared out is a bit obvious. Similarly, the show has its cake and eats it by refusing to flesh out its secondary characters. For all the preaching empathy and understanding, within the context of the show the Three Legged Man is still just someone to stare at and think "ooh, that's a bit weird."

On top of that, Bill Russell's book is yer typical by-the-numbers musical theatre dreck. Sometimes I feel like I'm really missing something when I'm watching shows like this - looking on with confusion as a rapt crowd applauds yet another cookie-cutter ballad or plodding lyrics overstuffed with terrible forced rhymes. On top of that the performances are comprehensively sucked dry of personality: close your eyes and this cast could be any white-toothed gaggle of stage school grads (with the exceptions of Chris Howell and Jay Marsh).

It's not that I don't enjoy musical theatre. I just don't like most of them - give me something with a little personality like Little Shop of Horrors or Matilda. Side Show is essentially a procession of hammer blow to the head songs with as much musical intelligence as a tractor, quickly leaving me trapped in bleary eyed boredom.

After the show I learned that Side Show's main reputation is of being a notable flop - having crashed and burned twice on Broadway. Please, someone slap a 'Do Not Resuscitate' tag around its neck(s) so nobody's tempted to have another go.

★★

Side Show is at the Southwark Playhouse until December 3rd. Tickets here.

Saturday, September 10, 2016

Punks don't fucking rollerskate. See, I was all excited when I first got the invite to Gregory Moses' punkplay, a show which very much sounded my thing. Then I read some promo material that mentioned that the entire play would take place on rollerskates. My expectations plummeted.

Good plays about punk are thin on the ground, the best coming in the form of small-scale one-man dramas (like Leon Fleming's excellent Sid, soon to return to Above the Arts Theatre). Most of the time you get some chintzy excuse for squeaky stage school warblers to dye their hair green and artfully distress some leather. Yes, I'm looking at you American Idiot.

Also slightly worrying is that punkplay is about American punk; British punk's dumber older brother. You can't pick holes in The Ramones, Dead Kennedys and Black Flag, but neither can you deny the scene's rapid degeneration into shitty suburban "screw you Mom and Dad! " mall punk like Blink 182, Sum 41 and, yeah, fuckin' Green Day. I'll take your classic snarling, corpse-thin London smack-addict punk any day of week - give me nihilism or give me death.

Mercifully, punkplay quickly proves punk as hell, displaying nice insight into punk's essential paradox: there are no rules, except for this massive conglomeration of unwritten (usually contradictory) rules. punkplay correctly approaches punk as a prism through which its characters define themselves, and comes to very different conclusions. Miraculously, it even eventually justifies the rollerskates.

Set in Reagan-era suburbia, punkplay follows teenagers Duck (Matthew Castle) and Mickey (Sam Perry). Life is stale and shrink-wrapped; studded with syrupy pop; parents threatening to parcel them off to military school; and bullies who punctuate their sentence with "faggot". Duck and Mickey resolve to become punk as fuck: dropping out of school, donning a mohawk/dyeing their hair and not letting their lack of musical talent stop them from forming 'The Zoo Sluts', who sound precisely as you'd expect.

Narrative quickly takes a back seat to a series of surreal vignettes. A beaten-up man in beaten-up leather is wheeled to centre stage where he croaks out a tale of violence on the road. An cough syrup induced dream sequence features the wrinkled head of Ronald Reagan atop a voluptuous girl's body, a talking polar bear and Andres Serrano's Piss Christ. Even the 'normal' scenes are studded with the surreal - clips from a distorted Russian videonasty called Amputee Museum, monologues about revolution via trucker boners and, in the midst of a fight, the two young punks make out under the discoball.

The cut-up style suits the punk aesthetic, the play doing whatever the hell it wants with scant regard for delivering a traditional theatrical experience. That dovetails neatly into the ramshackle aesthetic - props are white objects labelled "PORN", "COUGH SYRUP and so on, costume changes take place on set and, at one point, one of the characters appears to realise the artificial nature of the set and sees the audience watching him.

This really underlines the DIY aesthetic (also evident in the excellent 'zine' programme). The play is studded with tiny little touches that anyone who's lived through this will nod along to, perhaps recognising some element of their own past in these two boys. For my part, during a scene where they burn each other with cigarettes to prove their punk credentials, I found myself ruefully rubbing the cigarette burn scar on the back of my hand, a teenage me having had much the same idea.

Performance-wise, Castle and Perry do a great job of capturing teenage awkwardness and rebellion. Perry in particular is great, approaching Mickey as a tangle of limbs and angular posing. At times he resembles a cartoon character, loping around the stage with barely controlled elasticity. Castle is also excellent, slightly more aggressive and violent, looking like the dictionary definition of a classic punk. Also worthy of note are Jack Sunderland and Aysha Kala's side characters, each of which get powerful moments of emotion in which they shine amidst the chaos.

The cherry on the cake is a fantastic scene in which the analysis turns inwards and punk itself is deconstructed. Jack Sunderland, playing a kind of iconic uber-punk, explains that the scene is dead, that anyone trying to emulate it is a poser living in the past and that the true punks either died or worse, sold out. It's a solid takedown of a movement that was never designed to last beyond a hazy summer, punk's year zero approach giving it a kind of built in self-destruct sequence.

And yet, thirty years on, punk endures. Every fresh crop of teenagers defines their own punk rock, rebelling against the very baby boomers who once shoved safety pins before their noses before settling down in a nice semi-detached two up/two down in the country. What punkplay eventually concludes is that it's not the music you listen to, the clothes you wear or what shit you've smeared into your hair, punk is a state of mind shared by all that choose to participate: a genuine liberation from society's straitjacket.

So yeah, a great show. Check it out.

★★★★

punkplay is at the Southwark Playhouse until 1st October. Tickets here.

The cut-up style suits the punk aesthetic, the play doing whatever the hell it wants with scant regard for delivering a traditional theatrical experience. That dovetails neatly into the ramshackle aesthetic - props are white objects labelled "PORN", "COUGH SYRUP and so on, costume changes take place on set and, at one point, one of the characters appears to realise the artificial nature of the set and sees the audience watching him.

This really underlines the DIY aesthetic (also evident in the excellent 'zine' programme). The play is studded with tiny little touches that anyone who's lived through this will nod along to, perhaps recognising some element of their own past in these two boys. For my part, during a scene where they burn each other with cigarettes to prove their punk credentials, I found myself ruefully rubbing the cigarette burn scar on the back of my hand, a teenage me having had much the same idea.

Performance-wise, Castle and Perry do a great job of capturing teenage awkwardness and rebellion. Perry in particular is great, approaching Mickey as a tangle of limbs and angular posing. At times he resembles a cartoon character, loping around the stage with barely controlled elasticity. Castle is also excellent, slightly more aggressive and violent, looking like the dictionary definition of a classic punk. Also worthy of note are Jack Sunderland and Aysha Kala's side characters, each of which get powerful moments of emotion in which they shine amidst the chaos.

The cherry on the cake is a fantastic scene in which the analysis turns inwards and punk itself is deconstructed. Jack Sunderland, playing a kind of iconic uber-punk, explains that the scene is dead, that anyone trying to emulate it is a poser living in the past and that the true punks either died or worse, sold out. It's a solid takedown of a movement that was never designed to last beyond a hazy summer, punk's year zero approach giving it a kind of built in self-destruct sequence.

And yet, thirty years on, punk endures. Every fresh crop of teenagers defines their own punk rock, rebelling against the very baby boomers who once shoved safety pins before their noses before settling down in a nice semi-detached two up/two down in the country. What punkplay eventually concludes is that it's not the music you listen to, the clothes you wear or what shit you've smeared into your hair, punk is a state of mind shared by all that choose to participate: a genuine liberation from society's straitjacket.

So yeah, a great show. Check it out.

★★★★

punkplay is at the Southwark Playhouse until 1st October. Tickets here.

Friday, January 8, 2016

Grey Gardens explores a very special level of hell: family. Imagine being trapped at home forever, trapped in a decaying house with your decaying relatives and spiralling down down down into insanity, isolation and filthiness. What sets Grey Gardens apart is that its family are veritable A-listers of 20th century American aristocracy: the Bouviers (Jackie Kennedy being the most notable alumni).

In 1975, Albert and David Maysles released their direct-cinema documentary Grey Gardens, exploring the domestic lives of two upper-class recluses, a mother and daughter both named Edith Beale. The film explores the relationship between the women, living in squalor in athe titlular creaky, damp and dilapidated mansion. This place once hosted the creme de la creme of the East Coast social set, so audiences were shocked at the depths to which the former "girl who had everything" had sunk.

By 2006 the film had picked up a sizeable following in the gay community, leaving audiences spellbound by the forthright personalities, faded glamour and high camp. And so, it was adapted into a musical by Doug Wright, Scott Frankel and Michael Korie, to much acclaim. Now it finds it's way to London.

Translating a 'direct cinema' documentary into a musical is a steep challenge. The show tackles it by presenting a chronologically bisected narrative, the first act showing us the early 40s social pinnacle, with the second half digging deep into the 70s squalor.

Herein lies the core problem with Grey Gardens: the second half is ridiculously better than the first. I get what they're going for: ladling on pathos by showing us just how far these women have fallen and having them almost literally haunted by the ghosts of their glorious past. Theoretically this should work gangbusters, allowing us to tease out the origins of their mania and isolation.

In practice what you get is a lethargic, tension-free hour of musical theatre. We know exactly where this train is going and I was increasingly impatient to get there. Matters weren't exactly helped by the deeply tiresome queen-y caricature of George Gould Strong (Jeremy Legat). He's the older Edith's piano accompaniment and man-pet, but is apparently designed to deliver a steady stream of dusty innuendoes that lazily stand in for actual humour.

Once we've got this achingly slow set-up out of the way, things pick up. Post-interval is the meat of the night, fuelled by the excellent double-act of Sheila Hancock and Jenna Russell. The duo fizz together, all bitchy insecurity and flights of delusional grandeur leavened with sadness and loss. Russell in particular is downright hilarious as Little Edie, behaving as if she's performing to an invisible audience, which of course, she is.

Russell stalks the stage with weirdly compelling confidence, making outfits that look like she's drunkenly stumbled through Oxfam work. In these scenes you see the reason for the material's devout cult following; it's easy to feel the magnetic outsider-tug as she deems her bizarre clothes "my revolutionary costume" and angrily kicks against her snobby Hampton neighbours.

Shoring up things are a marvellous set courtesy of Tom Rogers, you can practically smell the black mould on the walls. Haphazard piles of trash dot the stage; the aristocratic debris of tattered furniture, ruined chandeliers and a lifetime's worth of chintzy gee-gaws. Jonathan Lipman's costuming is also worthy of attention, again primarily in the latter half. Everything is frayed and ripped, the characters engaged in a futile scrabble to keep up appearances in the face of domestic entropy.

As the curtain falls, Grey Gardens stands out as a remarkably distinctive 'downer' musical. This is a story that can only end miserably, and in the final moments are a kaleidoscope of misery, suffocation and loneliness. As someone who occasionally has to suppress his gag reflex at super-syrupy musical happy endings, I appreciate these dollops of darkness.

I'd like to recommend Grey Gardens more than I can. The two Ediths are absolutely fascinating characters and this show portrays them beautifully. That, in combination with top-notch staging, performances and nice songs should make this a no-brainer. But then there's that desperately dull first half.

In all honesty, my advice is to skip the first half and hang out in the bar until after the interval. You won't miss much.

★★★

Grey Gardens is at the Southwark Playhouse until February 6th. Tickets here.

Thursday, August 6, 2015

Berlin, 1928. Life in the Weimar Republic is politically, economically and culturally tumultuous. The economy is beginning to stagnate, unemployment is steadily rising, as is inflation, which will soon reach outrageous heights. On the bright side, Germany is going through a cultural boom, producing amazing cinema, jazz and modern art. Yet, just over the horizon you can hear the distant thump of jackboots...

For the most part, such worries seem pretty far away in The Grand Hotel. A temple to opulence, it's apparently insulated the miseries of the outside world. Staffed by immaculately turned out bellboys and frequented by sexy young flappers, aristocrats and businessmen it's a diamond in the necklace of Berlin. Yet all too soon, the problems of the outside world will seep through the gilded walls, corroding the luxury within.

This is promising stuff; I'm a known sucker for a musical with a political edge and I find the doomed Weimar Republic a fascinating piece of history. So it's a damn shame that Grand Hotel quickly proves to be a trifling piece of fluff populated by banal cliches. Straight from the stock characters file is the optimistic ingenue with hopes of screen stardom, the down-on-his-luck nobleman, the faded diva and the gruff ex-military cynic (with a gammy leg). It's like being stuck on a gigantic Cluedo board.

Worst of all is the cringeworthy Krigelein, a wealthy but dying Jew intent on one last taste of the good life before he pops his clogs. He's a teeth-gritting example of saccharine sentimentality, forever tossing out innocently upbeat comments about how wonderfully moral everyone around him is (spoiler, they're actually assholes), before periodically collapsing in coughing fits. Almost immediately after being introduced he reaches a height of obnoxious sweetness from which he never, ever descends.

One problem with reviewing this is that it's difficult to pick too many holes in the performances and staging. The cast is largely beyond reproach; Christine Grimandi does a decent job with the caricature ballet diva she's lumbered with and the striking Valerie Cutko as her gay admirer/assistant looks as if she's stepped straight out of a George Grosz painting. Enjoyable to lesser degrees are David Delve's grumpy Colonel-Doctor and Victoria Serra vigorously Charlestoning Flaemmchen.

The only genuine stumble comes with Scott Garnham's gentleman thief Baron. Down on his luck and indebted to gangsters, he's become a gentleman thief, seducing women to get at their jewellry. But though Garnham has a decent pair of lungs on him he's sporting an unfortunate scruffy half-beard and thus looks about as sexually dynamic as a damp dishcloth, which rather ruins the role.

The music and choreography is broadly competent. Some succour is given by the 8 piece band tucked away near the ceiling, but not even their rich sound can elevate a book of extraordinarily emotionally overegged songs. The dancing is a little better, especially when the cast launches into some flapper style click clacking across the stage, or when everyone is hustling and bustling around in the small space, but there's nothing here that hasn't been done better a hundred times before.

The individual cogs that make up Grand Hotel are all basically fine - but assembled into a machine it comes a cropper. The end product is a stodgy, over-cooked and largely indigestible musical with a facile historical perspective and an extreme reliance on creaky sentimentality. The closest I got to an emotional reaction was when a dancer accidentally spiked my foot with her high heel.

★★

Grand Hotel is at the Southwark Playhouse until 5 September. Tickets here.

Tuesday, July 7, 2015

The saga of Orson Welles is sobering. After his notoriously panic-inducing radio broadcast of War of the Worlds he went on to write, direct and star in Citizen Kane. Citizen Kane might be the greatest movie of all time; Welles wrote, directed and starred in it at just 26. Sadly from there it was a long, slow decline. Sure there was the odd ray of artistic sunshine, but he gradually collapsed into rotund obscurity, unable to secure funding for his projects and reduced to comedy cameos in crap movies. He ended his career angrily selling peas and playing a planet-sized cartoon robot before dying lonely, fat and broke in 1985. Poor Orson.

Orson's Shadow finds Welles (John Hodgkinson) in Dublin, 1960. He's on stage as Falstaff in a stage production Chimes at Midnight, though it's playing to depressingly empty houses. Arriving to lift him out of his funk is prominent critic and old friend Kenneth Tynan (Edward Bennet). As a connoisseur of quality he cherishes Welles' genius, finding it depressing that he's wasting away in obscurity. In an effort to drag him back to the mainstream he proposes that Welles direct Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros at the National Theatre.

The hitch is that it'll star Welles' rival and artistic enemy Laurence Olivier (Adrian Lukis). Olivier is caught in a love triangle, trapped between the demands of his glamourous but manic wife Vivien Leigh (Gina Bellman) and the cool professional beauty of Joan Plowright (Louise Ford). These fractious interpersonal relationships turn the rehearsal space into a battleground, with the elephantine egos of Welles and Olivier the heavy artillery.

It's fair to say that Orson's Shadow partially relies on its audience having some enthusiasm and knowledge of both Welles, Olivier and the broad strokes of theatrical history. A fourth wall busting introduction by Tynan efficiently sets the stage, giving us a broad overview of Welles' career to date. Later expository dialogue fills us in on Olivier's life, knitting together his tangled love life and paranoias. Even so, this could be pretty rough going for anyone coming in blind.

For those who've got a grasp of Welles' filmography and life though, there's a wealth of tiny touching moments. Listening to the man excitedly lie about getting a five picture deal with Universal off the back of Touch of Evil is sad, as is his scheming to raise funds from Eastern European financiers. Similarly humbling is his dogged insistence on not letting projects die; shooting a couple of minutes of Othello here and there, and working on Chimes at Midnight in secret.

Welles is a hugely recognisable figure, any performance of him treading a fine line between acting and simply mimicry. Hodgkinson, fortunately, stays just on the right side. In a brave bit of writing we hear him booming away before we see him. Hodgkinson can't quite achieve a perfect facsimile of Welles' supercilious, sonorous rumble, but he gets pretty damn close. Physically he's slightly hamstrung by an overly padded costume that doesn't really bear scrutiny at close quarters, but the illusion hangs together. Most crucially, Hodgkinson nails that 'Welles' twinkle' - mischievously smiling with his eyes alone. You can see it in Kane, The Third Man and F for Fake, and you can see it here.

Lukis' Olivier is slightly lesser in comparison. Played almost entirely for broad comedy he's a stereotypical pompous ham - the few snatches of 'acting' we see more reminiscent of William Shatner than 'the greatest British actor of the 20th century'. Still, as far as pompous hams go, the performance is above par. The script finds a man whose brain is knotted, heading off on tangents, with shaky confidence and the frustrating habit of dancing around the subject. He's never less than enjoyable to watch, though is more of a caricature than Hodgkinson's Welles.

It really shouldn't be understated how straightforwardly funny this play is. Be it Lukis' clowning it up with a duster, Welles coming out with outrageous sexual epithets or Tynan's bitchy asides about the worth of critics (which went down a storm on press night), but lurking just beneath the surface is a solidly melancholic core. The smell of failure and wasted talent hangs heavy over proceedings, with Welles' creative decline at taking centre stage. Everything comes to a head in an unexpectedly touching epilogue, where Plowright (the only person in this place who's still alive), gives the characters a quick tour of their pretty depressing futures.

It's quietly heartbreaking to see Welles learn that over the last 25 years of his life he'll only make one more movie. That sadness turns to excitement when he learns that the movie will be Chimes at Midnight. Welles has been confidently blustering through the rest of the play, but here, finally, we see him vulnerable and childlike. "Is it any good?" He tentatively asks.

In its best moments Orson's Shadow achieves an eerie verisimilitude that makes you feel as if you're in the company of the great man. In its worst it's merely a well-written, comedic farce about two huge egos bonking heads. If you're at all interested in Welles it's an easy recommendation. If you're not, then go watch Citizen Kane. Seriously, watch it. It's not some unapproachable dated black and white melodrama - it's goddamn outstanding and actually straight-up entertaining. You'll laugh. You'll cry. You'll say "Ahhhh, so that's what the Simpsons was referencing...". Done? Good. Now come and watch Orson's Shadow for the rest of the story.

★★★★

Orson's Shadow is at The Southwark Playhouse until 25th July 2015. Tickets here.

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

In Gods and Monsters ragged chunks of history, anatomy, sexuality and cinema are stitched together into a chaotic whole. The result is a chronologically tangled, confusing soup of emotions and memories, filtered through a crumbling mind. The play, adapted from Christopher Bram's biography Father of Frankenstein (later adapted to film), shows us the last weeks of James Whale, most famous for directing Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

Set in 1957, we first meet the elderly but far from decrepit Whale (Ian Gelder), while recovering from a stroke. Though he's suffered no physical impairment, he has excruciating headaches and often finds his thinking slowed, muddy and confused. Powerful, long-buried memories surface unbidden and shock him with their intensity. Doctors are clueless, his maid is concerned and his medication merely tranquillises him. Trapped in this mental no-man's man he searches desperately for something to occupy his mind.

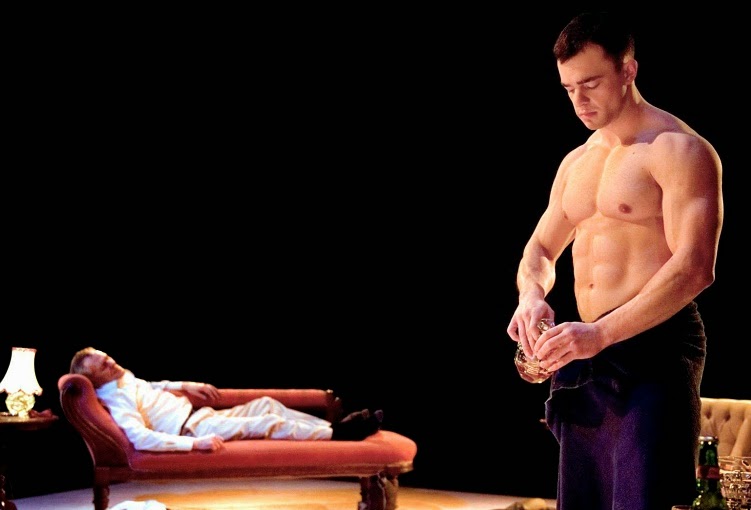

He finds that distraction in his gardener, Clayton Boone (Will Austin). The openly gay Whale regards Boone with unbridled lust. You can see his point, the butch Boone is the very model of homoerotic sexuality - looking like a Tom of Finland sketch come to throbbing life. The two men strike up an unlikely friendship after Boone agrees to pose as an artistic model for Whale. Boone's mere presence provides succour for Whale, taking his mind from his medical problems and awakening a libidinous tingle. But complications soon mount, with Whale's mind inexorably deteriorating past, present and future melt together, his neuroses and fantasies crystallising into Boone's buff physique.

Using thrust staging, director Russell Labey places the audience at the borders of Whale's lounge. Surrounded by cool white marble, tasteful mahogany and a decadent chaise longue the set is a model of restrained elegance. Gelder's Whale fits the space like a glove, his linen suits and 'Englishman abroad' style combine to make him look grown out of the floor itself. Conversely Boone sticks out like a sore thumb, his Levis and filthy vests marking him as an interloper in Whale's refined world.

|

| James Whale (Ian Gelder) |

In a clever touch, the marbling of the walls and floor recalls brain tissue; light pink riddled with red capillaries. Peering through is Boris Karloff's iconic monster, casting a gloomy gaze over proceedings. These elements neatly outline that we're watching a hallucinatory, psychological reality that literally takes place inside Whale's head as much as the 'real' world. This makes the moments we slip back in time affecting and morose, the elderly Whale solemnly observing the misadventures of his younger self.

Beginning with teenage sexual experimentations we soon move forward to his experiences in the Great War. These moments, aided by excellent projection work from Louise Rhoades-Brown, are intense and ethereal, the echoes of mortar shells ringing across time. As the narrative progresses, repressed memories of pain and torment bubble to the surface of Whale's consciousness, kindled by Boone's masculine ex-soldier.

As Whale's condition becomes more severe, he becomes increasingly unable to distinguish between fantasy and reality. It's here that the echoes Frankenstein emerge, Whale casting himself as the doomed Victor Frankenstein and imagining Boone as a hulking, murderous monster. Eventually he begins subconsciously re-enacting elements of Shelley's tale, praying that Boone will become a Golem and grant him release from this misery.

|

| Lt Whale (Will Rastall)) and Barnett (Joey Phillips) |

This means the play simultaneously functions on three distinct levels: the reality of Whale's last days, the jagged fantasies of his hallucinations and the subconscious re-enactment of Frankenstein. This is cracking theatre; you immediately sense that this is a production where every element has been intelligently constructed to elevate the whole, all aided by the two compelling performances of Gelder and Austin.

Gelder's Whale is, from minute one, a fully realised human being. He's a man who's disorientated by the ground shifted under him, you sense his strong self-image and the terror by the mask of civility slipping away and leaving him a drooling shell. In his lengthy monologues and recollections Gelder keeps us in rapt attention, drawing from apparently bottomless wells of charisma. Given that Whale is, on paper, a dirty old man leching after young flesh, it's faintly miraculous that Gelder effortlessly keeps him eminently likeable.

Will Austin impresses more with his physical presence than his acting, but damn what a physical presence. I'd say he's built like a brick shithouse, but that barely covers the half of it. His physique is such that there were muffled gasps when he first took the stage, and once again when he took his top off. The bodybuilder look combined with his gentle personality contributes to a powerful, irresistible sexuality. This is so powerful that everyone in the audience, regardless of their inclinations, sympathises with Whale's desires. Soon the very sound of Boone's lawnmower off-stage contributes to a Pavlovian reaction in both Whale and audience, setting us drooling in anticipation of Boone's presence.

This is, by any reasonable standards, a wonderful piece of theatre, but not a perfect one. For the most part the thrust staging is carefully judged to give audiences an interesting view no matter where they're sitting. But there are certain seats that offer frustratingly restricted views, important moments blocked by furniture or played with the character's back to the audience (incidentally, I'd recommend sitting stage left). Another slight quibble is the performance of Lachele Carl as Whale's devoted maid Maria. A broad Hispanic stereotype, the character is played for laughs, the pidgin English gags feeling awkward and old fashioned.

This aside, Gods and Monsters is one of the finest things I've seen on stage this year so far. Practically every millimeter of set, staging, performance and script is precision-tuned towards a single aim, a palpable and attractive eye for excellence. Emotional, intelligent, erotic and horrifying; this is a bracing gust of fresh air on the London stage.

★★★★

★★★★

Gods and Monsters is at the Southwark Playhouse until 7th March. Tickets £18 (£16 concs) available here.

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Forget war in Yugoslavia, presidential elections and economic turmoil, in 1992 one headline stood head and shoulders above the rest: 'BAT CHILD FOUND IN CAVE'. The front page showed a screaming, befanged, bug-eyed, pointy-eared child. A star was born!

Of course, the newspaper with the scoop was (now sadly defunct) The Weekly World News, so perhaps the factual accuracy of the story was a bit... iffy. But in the face of such a compelling discovery who cares about silly little things like the truth? Since his discovery the WWN kept its readers closely informed as to what this mysterious Bat Boy was up to, including running for political office, aiding in the capture of Saddam Hussein, endorsing first John McCain and then Barack Obama for President and most recently protesting in favour of gay marriage in California.

His bizarre fame growing, it was inevitable that stage boards would one day lightly creak to the weight of bat-feet. And so it was that in 2001 Bat Boy the Musical opened off-Broadway in New York, followed by a six month London run in the Shaftesbury Theatre in 2004. Now, after nearly ten years, it returns in all its demented, trashy glory.

The musical tells the tragic, jumbled and outrageous tale of the Bat Boy (Rob Compton). We open in his lair; the damp depths of a forgotten cave system. Provoked he attacks some dumb teenagers, resulting in his capture and delivery to the house of local vet Dr Parker (Matthew White). His wife Meredith (Lauren Ward) immediately begins caring for this disturbed, helpless individual and she's soon joined by her initially sceptical teenage daughter Shelley (Georgina Hagen).

But dark things are afoot in the small town of Hope Falls (soon to be Hope Fails). The cattle the town relies on are mysteriously dropping dead and the ones still alive aren't in particularly good shape either. Bat Boy becomes the scapegoat for their problems, despite the fact that Meredith's love and care has transformed him into an erudite yet naive young man. Even Shelley has begun to look beyond the fangs, hairless head and pointy ears and noticed something rather hunky about this Bat Boy...

The basic story of a 'freak' being introduced to suburbia, briefly embraced then demonised owes an awful lot to Edward Scissorhands. For much of the first act Bat Boy the Musical hews suspiciously close to Tim Burton's classic film, to the point where you get an inkling that you've seen this story done before (and better). But after the slightly humdrum first act things pick up a bit, plunging headfirst into demented horror-comedy that feels like The Jerry Springer Show by way of Ed Wood.

This style, 'Tabloid Gothic', sends us down a twisty tunnel full of gruesome murders, mad doctors, bestial love potions, burning bodies and incestuous union. Though still roughly predictable there's enough John Waters style bad taste glee to keep the audience in a perpetual state of eyebrow-raising at whatever crazy wrinkle in the plot will crop up next. Anyway, it's difficult not to enjoy a musical where the lead strolls onto the stage midway through devouring a severed cow's head.

Nearly all of the show's success rests on the the hunched shoulders of Rob Compton's Bat Boy, who from a technical and performative standpoint is the obvious centrepiece. The excellent prosthetics mean that we unquestioningly accept him as real the moment we come across him. The thin latex that allows him to be illuminated from behind, the high spotlight causing them to glow either side of his head. His fangs are impressively realistic too, predatory and dangerous, but never in the way of his performance.

And boy what a performance. Channelling the hunched physicality of Andy Serkis' Gollum, the midnight sinisterness of Murnau's Nosferatu and later, a smidge of the effete, snooty intellectual, Bat Boy is fascinating to watch. As he scuttles and scrabbles around the stage Compton's shoulder blades slice the air like dorsal fins, suggesting wings about to sprout from within. Even when he's upright and besuited there's an air of the alien to him, his body moving around under the clothes with muted sexual awkwardness. The rest of the cast are no slouches (I particularly enjoyed Simon Bailey's travelling preacher), but it's the Bat Boy we're here to see, and at least here the show delivers in spades.

It's not all peaches and cream though, the songs are mostly uninspired and oddly produced. There's a low-fi plasticky quality to the sound system that doesn't so much get toes tapping as it does necks straining to decipher what's being sung. On the odd occasion it finally comes together; Let Me Walk Among You is beautifully written, scored and performed. On the flipside, regrettable incursions into rap and what sound like MIDI guitars made my ears quiver in annoyance.

There's also never quite nailed down tone: the audience is never quite sure whether we should caring about the characters or giggling at their demises.Bat Boy himself is straightforwardly sympathetic, but a lot of the gags are are based around sniggering at small town stereotypes whose misery and gruesome deaths are the height of hilarity. This is, I suppose, the essence of tabloid rubbernecking and so appropriate for a show adapted from a supermarket checkout rag, but it makes it very difficult to care about what's happening even though we're apparently supposed to. There's also the odd dud joke: the OTT panto drag feels a bit desperate and the comedy rape is questionable at best.

Bat Boy the Musical isn't exactly a bad show. If your desire is to see a half boy/half bat then this delivers in spades. But there's a big bushel of things that don't quite run as smoothly as they could. Perhaps these are inherent to the show as written, perhaps it's due to seeing it early in the run or maybe its partly the staging (relegating key exposition to a video projection feels a touch lazy). But despite the frequent stumbles, wobbles and trips the show stays on its feet and just about squeaks into entertaining.

Bat Boy the Musical is at the Southwark Playhouse until 31st January. Tickets here.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

That I walked out of Grand Guignol with blood spattered across my face tells you everything. It happened while a woman was convulsing in terrified agony as her eyeballs were gouged out, meaning that I, sat on the front row got a sprinkling of the red stuff. Naturally I was pleased as punch; for the Grand Guignol isn't a place you attend to appreciate the subtleties of the human condition, to revel in high minded intellectualism or to appreciate aesthetic beauty.

No, it's where you tremble as you wade hip deep through ichorous gore!

Thrill to a cacophonous symphony of screams!!

G-g-g-ghoulishly grimace at monstrous actions conceived beyond the realm of sanity!!!

Huh.. I went a bit Vincent Price for a moment there. Well, with Halloween just around the corner it's difficult to resist a touch of the macabre slipping in, something encouraged - nay - demanded - at Grand Guignol, a play as ghoulish as it is hilarious, demented as it is sharp and crammed to bursting point with gooey horrors of all kinds.

Set in early 20th century Montmartre, the play takes place behind the scenes of Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol, a venue that, more than 50 years after it's closure remains the byword for over-the-top blood n' guts. Our cast of characters are the real-life talent behind the theatrical phenomenon; Max Maurey (Andy Williams), the pragmatic and pugnacious owner of the establishment; Henri (Robert Portal), male lead and colossal ham; Maxa (Emily Raymond), female lead and "the world's most assassinated woman"; Ratineau (Paul Chequer), gore designer and Tom Savini of his day and; Andre De Lord (Jonathan Broadbent), the only playwright an imagination twisted enough to concoct these diabolical phantasmagoria.

Tossed into their world of plaster limbs, rubber intestines and buckets of (stage) blood is nervy psychologist Dr Alfred Binet (Matthew Pearson). He's in charge of an asylum that's exploring the limits of the human condition and seeks to understand De Lord's mind; to unravel what is about his past that allows him to summon up such theatrical devilry. This all comes in combination with the mysterious murders of the 'Monster of Montmartre', who prowls the streets disembowelling his victims and carving pentagrams into their lifeless corpses.

Given the grim subject matter and warped characters, it's perhaps surprising that above all else, Grand Guignol is an extremely lighthearted farce. These characters are all extremely broad types, their personalities firmly cranked up to 11. So Maxa isn't just a talented horror actor, she's a twisted gorehound increasingly unable to discern the theatre from reality. Henri isn't just a lead actor, he's an egomaniacal, impossibly verbose blowhard. De Lord isn't some talented playwright, he's haunted by the ghost of Edgar Allen Poe and fuelled by barely suppressed childhood trauma.

The extremely talented cast navigate this material like they're born to play these characters, every performance perfectly pitched for maximise the comedy potential of the material. I particularly enjoyed every single perfectly enunciated line recited by Robert Portal, whose face pushes the limits of expressiveness. I'd read that this play had been performed as a straight horror a couple of years ago, something practically impossible to imagine after seeing this. To spoil these gags would be a sin, so I'll refrain from listing all my favourites, but one stab at theatre critics in particular brought the house down.

Fortunately, Grand Guignol being so damn funny doesn't preclude it from also being horrifying. What you quickly realise is that stage violence and gore has a different quality to that of cinema or television. Seeing a person have their throat slashed before your very eyes, blood oozing from their wounds as they twitch their last mere meters away is much more intense an experience that anything you'd see in over the separation of a screen; the harsh stage lighting casting gruesome shadows across their wounds.

The sensible, logical part of you is telling you that it's obviously fake, that you're looking at a rubber prop with a pipe in it, but some primal, caveman part of the brain sees the sticky crimson blood and reacts instinctively, sending unavoidable tingles of terror reverberating around your body. It's this sensation, laughing at the gory audacity that makes the comedy feel so alive.

Best of all, this show does a decent job of roughly emulates the original Grand Guignol. These characters were all real people, and De Lord really did work with a psychologist, named Binet to maximise the horror potential of his plays. Notably, all the miniature vignettes we see are actually bitesize summaries of De Lord's work, making this both entertainment and theatrical history lesson all in one.

So I deeply dug this; a fantastic production that's perfectly timed for Halloween. As the sun sinks further over the horizon and temperatures drop, get yourself down to Southwark and suffer some real chills! Highly recommended.

Grand Guignol is at the Southwark Playhouse until the 22nd of November. Tickets here.

Huge thanks to Rebecca Felgate at Official Theatre for the ticket. Details here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)