Recent Articles

Home » Posts filed under videogames

Showing posts with label videogames. Show all posts

Showing posts with label videogames. Show all posts

Friday, August 4, 2017

For decades we've been told that playing video games will turn us into bloodthirsty, violent monsters with the attention span of a gnat. But what if video games were actually, genuinely, good for you. This is the core of Amy Conway's Super Awesome World, which makes a convincing case that those hours spent blowing away the forces of hell, descending into dark dungeons and repeatedly rescuing princesses might not have been wasted.

We begin with a potted history of Amy's history of gaming. In 1994 she was gifted a NES, on which she lost herself in the worlds of Super Mario World and The Legend of Zelda. The crude yet evocative 8-bit graphics were perfect imagination fuel: allowing her to transcend dowdy reality and spend time in a place where your actions matter: where you really can save the world.

The show uses the retro gaming aesthetic to tell the story of Amy's "quest for good mental health". She repeatedly goes back to her time spent volunteering for Samaritans, explaining that she sees each chat as equivalent to a game: you just have to say the right thing to advance to the next conversation 'level'. The audience also gets hands-on examples of the pleasure of play, participating in short, fun physical exercises in which we get to know the people around us.

It's often fascinating, especially when Amy lays out why she thinks gaming is good for mental health. The argument goes that games provide a structured environment with clear, achievable goals and a constant system of reward. This is contrasted with the chaotic and confusing real world, in which the rules are opaque and the goals always shifting. This made me reflect on the benefits games might have given me over the years. I thought of my time with notoriously difficult adventure game Dark Souls, in which death is frequent, quick and generally brutal. But while it's hard it's also scrupulously fair. If you pay attention, approach the game with patience and keep your cool, you can vanquish even the most ferocious monster.

This nicely ties into the games we play through the show, which emphasises teamwork, communication and mutual support. In one, I got a chance to taste a morsel of Amy's work with the Samaritans. She was blindfolded and had to cross the stage with my assistance. Here I was trying to deliver precise and useful advice to someone who couldn't see where they were going, who had placed their trust in a complete stranger and whose fate ultimately rested in my hands.

This is just one example of the care that's gone into making Super Awesome World coherent. The show goes to some pretty heartrending places, Amy eventually her soul and encouraging us to share our most vulnerable moments. This isn't a show about big performances - Amy sometimes seems quite shy on stage - but there's a palpable honesty that pays off gangbusters in these closing moments.

While the show is eager to sing the benefits of gaming, I couldn't help but think of the other side of the coin. I think that artificial sense of achievement video games provide is genuinely addictive - for example, the dopamine *whoosh* of levelling up in World of Warcraft has consigned countless teenagers to an isolated, pallid adolescence. Is there a danger that getting accustomed to a life spent in virtual worlds where you're always the legendary hero makes unfair 'IRL' that much more mentally unbearable? In a video game you can try and try until you inevitably triumph. Reality is rarely so accommodating.

But maybe that's a topic for another show. Amy Conway's perspective on gaming is original and accurate - not to mention that she avoids descending into obscure references. On top of that, obvious care has gone into capturing the 8-bit aesthetic in the on stage graphics and sound (I was particularly pleased to hear the soothing bleeps of DuckTales' The Moon as I took my seat). Super Awesome World isn't always an easy watch, but it's smart and satisfying stuff. Recommended.

Amy Conway's Super Awesome World' is at Summerhall until the 27th of August. Details here.

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

Encountering London in videogames is often winceworthy. Whether it by design or technological limitations, games often present a tourist's guide to London - taking in the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace and Piccadilly Circus with a couple of badly voice-acted cockneys thrown in for good measure.

It's rare that a game manages to capture even a smidge of London reality; glass and aluminium dominating imperial Portland stone and the vestiges of medieval buildings; that distinctively London psychic mood of short-term impatience and long-term tolerance; the class, religious and racial divisions that carve up the neighhourhoods and the simple Darwinian scrabble for shelter, food and money that fuels the human engine of the city.

At last night's lecture, panelists Jack Gosling, Jordan Erica Webber and Tristan Donovan attempted to pin down what makes London tick in videogames, giving us a guided tour through the city's appearances in the medium, from the bedroom coders of the 80s to modern triple A blockbusters.

Tristan Donovan kicks things off by dragging us back into gaming's primordial ooze with the 1978 text adventure Pirate Island. Our capital's first appearance in the digital medium is the inauspicious introductory sentence "I am in a flat in London". It goes on to explain that you can see a bottle of rum, some trainers and a sack of crackers (now that's a scene I can relate to). Similar text adventures followed, most notably social satire Hampstead, which skewered Thatcherism and set the stage for a continuing theme of gamified London-set class struggles.

|

| Promising beginnings. |

|

| Lara explores Aldwych Tube Station |

Text gave way to single colour sprites, which gave way to 16-bit colours and parallax scrolling, which eventually ceded to texture mapped polygons. It's here designers and developer first had the irresistible urge to translate some glimmer of London reality into games. An interesting entry is Core Design's 1998 Tomb Raider III, in which the impeccably British adventurer returns home to explore blocky renderings of the British Museum, the (then relatively recently) abandoned Aldwych tube station and the rooftops around St Paul's Cathedral.

|

| Bosh! |

This lit the touchpaper for the still-ongoing trend to create realistic virtual Londons to fight, race and generally cause havoc in. A notable entry was Team Soho's 2002 release The Getaway, which is essentially Grand Theft Auto by way of Guy Ritchie. The game itself is a bit of a dog, but it's at least impressive for trying to accurately model central London from Hyde Park all the way up to Shoreditch High Street. Problem is, the PS2 couldn't render the hustle and bustle of the city, leaving the streets sterile and bereft of life - falling into a kind of urban uncanny valley.

Most modern games, outlined by Jack Gosling, opt to present a tightly choreographed smaller areas, sidelining scope in favour of attention to detail. A prime example is Naughty Dog's 2011 Uncharted 3: Drake's Deception, in which Nathan Drake begins his adventure fighting skinheads in an East London boozer, before descending into an abandoned tube station/secret occult library. Though the game gives us a 'wow moment' with its neon vision of the City of London's skyline, Jordan Erica Webber explains just how much work into virtually recreating the stained urinals of some crappy pub. Though the player will probably be more occupied with the tracksuited thug punching them in the face, the level is crammed with location appropriate graffiti, grotty props and general dank. You can practically smell the stale piss..

|

| I preferred Nanda Parbat. |

Other London set games exploit its history. Countless Sherlock Holmes games have conjured up foggy gas-lit Victorian streets, and other titles offer a smattering of alternative Londons invaded by Nazis, aliens or sometimes alien Nazis. Most prominent is Ubisoft's 2015 globe and time-trotting Assassin's Creed series winding up in Victorian London. The game map encompasses vast swathes of the city, giving people a peek at London past. On top of that, we're allowed to frolic with luminaries like Dickens, Darwin and Queen Victoria - even undertaking missions alongside Karl Marx as a kind of ragged trousered exsanguinist.

In a perverse twist, a believable virtual historical London is more achievable than contemporary virtual London. For one, we're all tourists in the past, the haze of time neatly sidestepping nitpickers whose immersion might be shattered by a phone box being on the wrong corner. For another, perhaps it is simply impossible to render a believable London in a videogame - and even if you could would the tangled street layout, crammed pavements and neverending traffic even make for a fun gaming space?

|

| It's weird to look at real-life buildings and think "I stabbed someone on top of that thing". |

For my part, I find encountering London in games fascinating. It's one of the few ways you can explore the city through other people's eyes: finding myself curious as to what neighbourhoods they choose to render, what architecture caught their attention, what litters the streets or simply what dreams London sparks inside them. The duller ones manacle you to the top of a tour bus, but the best come within a whisker of capturing what it feels like to walk these grey streets. And who knows what the future may hold.

An excellent talk and a great introduction to what looks like a fascinating programme.

London and the History of Videogames is part of CITY | SPACE | VIDEOGAMES. More information here.

Thursday, October 23, 2014

It'd be a shame if the London Film Festival were entirely pretty actors in expensive clothes prancing around on a drizzly Leicester Square red carpet. Sometimes you want to dig a little deeper. That's where 70 year old Czech born German experimental documentarians come in. Screened as part of the Experimenta strand, the late Harun Farocki's Parallel I-IV is a series of short documentaries that explore the politics, imagery and narrative limitations of videogames.

I enjoy the odd videogame but I have no illusions as to their worth. Maybe one day they will evolve into a worthwhile activity, but as it stands they're glorified Skinner boxes designed to dole out doses of emotion. The most powerful illusion that a videogame creates, the barometer by which we measure their quality, is the creation of a false sense of accomplishment (popularly known as 'gameplay'). Whether it's becoming a champion race car driver, winning the world cup or becoming the top crime boss in a city, what videogames ultimately simulate best is success.

In this regard the best videogames act as opiates, granting the player a temporary tingle of fake happiness that quickly fades, needing to be supplemented by another fix. And then another, ad infinitum. There's a reasonable argument that other media offer the same thing; the adrenaline rush of a good action movie or the shiver down the spine when those star-crossed lovers finally smooch. But whilst other media are often able to make you more intelligent and give you new perspectives on the world, videogames tend to make you dumber through a seductive narrative of individual empowerment.

With that in mind, the key to the Parallel series success is exploring videogames from an outsider's perspective. Harun Farocki, having no emotional attachment to the medium, comes at it with a clean mind, free from preconceptions as to how games work or what conditions of 'good play' are. What interests him is the idea of poking at the edges of virtual worlds, observing behavioural algorithms and examining methods of representing reality.

An aspect of games that's often overlooked is the accepted boundaries of behaviour for a player. Experienced players know the ropes, for example, they instinctively grasp the boundaries of a level and capabilities of their avatar and, so, over the course of normal play, won't try to squeeze through barriers that demarcate where the game world 'ends'.

In footage from L.A. Noire we follow a policeman around an impressively rendered 1940s Los Angeles, the only obviously unrealistic thing the impassable roadblocks preventing the player from leaving the city. A seasoned player wouldn't give these a second thought, yet Farocki drives his virtual cop car directly into them over and over again. We see a similar process in Red Dead Redemption, a cowboy meanders his way across an epic prairie, only to plunge to his death when he crosses a certain, unmarked point on the map. Open world games sell themselves on player freedom, yet Farocki exposes that freedom as strictly defined.

Farocki shows us repeated clips the player behaving in ways that expose the limits of the game. The most striking are his manipulations of NPC behaviour. In Mafia 2 he leads the player character towards an old woman who's smoking a cigarette, standing directly in front of her and blankly staring. In the course of normal gameplay we'd hear a short voice clip from her telling us to get out of her way and we'd move on. In Parallels she begins cycling through repetitive voiceclips and animations, smoking an infinite cigarette. There's a performative aspect to videogames that often goes overlooked; the player encouraged not to shatter the illusion of the gameworld by playing their role as the designer expects.

Examples like these expose the ideological limitations of the medium, which arise from the basic need for the player to be at the centre of events. This means the vast majority of games present a solipsist world in which the player is God (even games with thousands of simultaneous players tailor the experience of each player to tell them they're 'the chosen one'). Players thus become immortal and nearly omniscient - everything in the gameworld designed to entertain them and them alone.

Given that hardcore gamers immerse themselves for endless hours in worlds where they are the centre of attention is it any wonder that their identities become warped? In the ongoing #Gamergate farrago, self-styled 'gamers' have reacted with astonished horror at their pastime being exposed to cultural analysis, reading criticism of their entertainment products as criticism of themselves. They are trapped in a confused loop: "The feminist says the game is sexist, which means that I am sexist, but I know I am not sexist, therefore the game is not sexist. If the game is not sexist then the criticism is false, therefore the feminist is a liar therefore she is a whore therefore fuck u whore i will rape u so hard."

Reactions like #Gamergate show us the extreme consequences of videogames' operant conditioning, the player's personality becoming accustomed to an endless cycle of masturbatory, egocentric wish fulfilment that's easy to achieve in the virtual world but impossible in reality. Farocki's film scratches at the surface of this, but it only takes the tiniest effort to peek beyond the veil and expose videogames as a medium with an inherently limited scope.

Consider this: after 35 years of cinema we had the formal experimentation of Eisenstein and the narrative and technical genius of Welles' Citizen Kane. After 35 years of videogames we are still largely mired in corridors full of people to shoot with guns and B-Movie narratives. Graphics have approached photorealism but we haven't progressed beyond Space Invaders with its waves of slowly approaching targets to eliminate. Perhaps the medium will eventually take a great leap forward (games like Minecraft present promising, if embryonic, possibilities), but from a 2014 perspective that leap feels a long way away.

In footage from L.A. Noire we follow a policeman around an impressively rendered 1940s Los Angeles, the only obviously unrealistic thing the impassable roadblocks preventing the player from leaving the city. A seasoned player wouldn't give these a second thought, yet Farocki drives his virtual cop car directly into them over and over again. We see a similar process in Red Dead Redemption, a cowboy meanders his way across an epic prairie, only to plunge to his death when he crosses a certain, unmarked point on the map. Open world games sell themselves on player freedom, yet Farocki exposes that freedom as strictly defined.

Farocki shows us repeated clips the player behaving in ways that expose the limits of the game. The most striking are his manipulations of NPC behaviour. In Mafia 2 he leads the player character towards an old woman who's smoking a cigarette, standing directly in front of her and blankly staring. In the course of normal gameplay we'd hear a short voice clip from her telling us to get out of her way and we'd move on. In Parallels she begins cycling through repetitive voiceclips and animations, smoking an infinite cigarette. There's a performative aspect to videogames that often goes overlooked; the player encouraged not to shatter the illusion of the gameworld by playing their role as the designer expects.

Examples like these expose the ideological limitations of the medium, which arise from the basic need for the player to be at the centre of events. This means the vast majority of games present a solipsist world in which the player is God (even games with thousands of simultaneous players tailor the experience of each player to tell them they're 'the chosen one'). Players thus become immortal and nearly omniscient - everything in the gameworld designed to entertain them and them alone.

Given that hardcore gamers immerse themselves for endless hours in worlds where they are the centre of attention is it any wonder that their identities become warped? In the ongoing #Gamergate farrago, self-styled 'gamers' have reacted with astonished horror at their pastime being exposed to cultural analysis, reading criticism of their entertainment products as criticism of themselves. They are trapped in a confused loop: "The feminist says the game is sexist, which means that I am sexist, but I know I am not sexist, therefore the game is not sexist. If the game is not sexist then the criticism is false, therefore the feminist is a liar therefore she is a whore therefore fuck u whore i will rape u so hard."

Reactions like #Gamergate show us the extreme consequences of videogames' operant conditioning, the player's personality becoming accustomed to an endless cycle of masturbatory, egocentric wish fulfilment that's easy to achieve in the virtual world but impossible in reality. Farocki's film scratches at the surface of this, but it only takes the tiniest effort to peek beyond the veil and expose videogames as a medium with an inherently limited scope.

Consider this: after 35 years of cinema we had the formal experimentation of Eisenstein and the narrative and technical genius of Welles' Citizen Kane. After 35 years of videogames we are still largely mired in corridors full of people to shoot with guns and B-Movie narratives. Graphics have approached photorealism but we haven't progressed beyond Space Invaders with its waves of slowly approaching targets to eliminate. Perhaps the medium will eventually take a great leap forward (games like Minecraft present promising, if embryonic, possibilities), but from a 2014 perspective that leap feels a long way away.

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

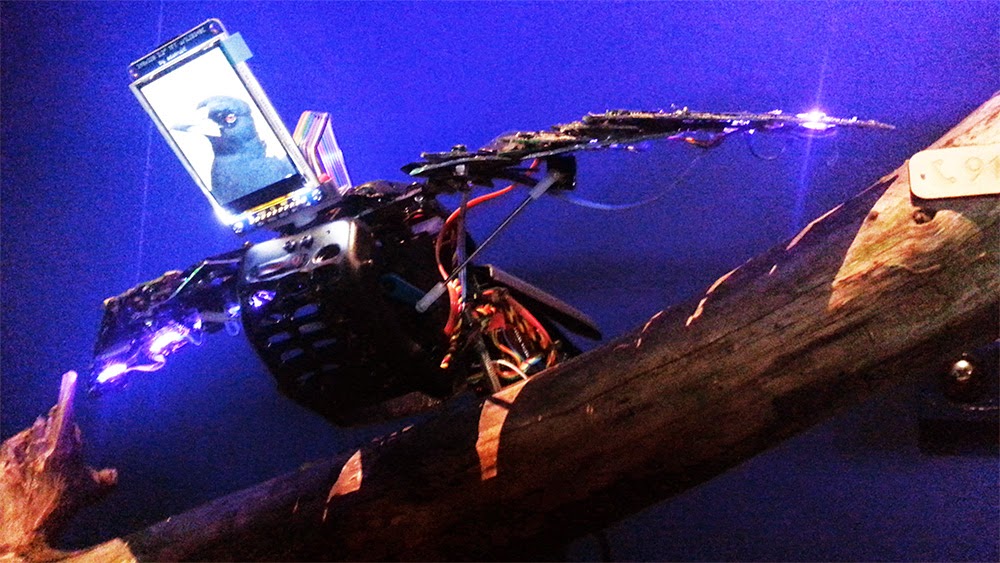

Digital Revolution is an unreasonably entertaining exhibition. Within the Curve Gallery at the Barbican centre they've crammed a crazy amount of eye-catching, imaginative and straight up fun technological trinkets. By the time you've come to the end of the exhibition you'll have had steam billowing from your eye-sockets, been transformed into a birdcreature and flown away and been sung at by the giant creepy Egyptian-styled head of will.i.am. But first a game of Pong.

At first it's like you've walked into a particularly busy branch of Virgin Megastore circa 1995. Bathed in futuristic blue light, monitors glow from steel racks and the air is filled with iconic synthesised videogame blips. Somewhere Sonic the Hedgehog has dropped his rings, Mario has gobbled a mushroom and the Russian folk song Korobeiniki (immortalised in gorgeous DMG-CPU-03 GameBoy synth) floats across the room. It's as if ten-year-old-me has died and gone to heaven. Projectors around the room show some of the greatest hits of 90s tech; the T-Rex from Jurassic Park, Lara Croft diving through flooded tombs - even beloved obscurities like Parappa the Rapper get their moment in the sun.

|

| Someone enjoying Super Mario Bros. |

It's peculiarly touching to see all these childhood favourites immortalised in a gallery - what was once regarded to be trivialities now behind plexiglass with a little description alongside explaining its heritage and cultural import. As we move through the exhibition we quickly realise that these 8, 16 and 32 bit classics represent the testy first dabbles of culture's toes in the digital sea - the early years when it began to realise the joy of shifting pixels.

The rest of the exhibition is devoted to the potential of technology to elevate mankind, appreciate the world in new ways and explore our rapidly growing technological legacy. It's this last aspect that this exhibition really opened my eyes to. By its very nature the internet is transitory - a website changes its design and (aside from archived screenshots) it vanishes forever. As long-forgotten servers die, so to do the dusty bytes hidden away on them. Experiencing these early webpages feels somehow important to understanding the modern internet. I was particularly impressed by Hi-ReS!'s website for Requiem for a Dream which uses Flash 4 magnificently in recreating the style of the film as a page. You can experience the archive of this here - a vintage yet still lovely slice of internet art.

|

| Requiem for a Dream website - Hi-Res |

The most impressive example of trawling through the lost internet is Richard Vijgen's The Deleted City. If you were online in the mid to late 90s you weren't anybody unless you had a GeoCities page crammed full of flaming skull gifs and "Under Construction" banners. As the internet evolved and social media began to grow, people quickly abandoned the site, first to MySpace and then Facebook, leaving behind an internet ghost town. In 2009 the death sentence was pronounced; the entire community was to be deleted. In a heroic effort, a team scoured the servers of data before deletion - amassing a 650 gigabyte file.

|

| The Deleted City - Richard Vilgen |

In The Deleted City you can explore this archive, navigating through the cyberboulevards and zooming in to see what you can find. I unearthed an enormous cache of bitty, low-res pictures of Sporty Spice and a bizarrely comprehensive history of the haircuts of The Backstreet Boys. Vilgen describes his work as a "digital Pompeii", and much as we stare at ancient Roman graffiti and try to put ourselves in their sandals, perhaps future generations will ponder Bonzi Buddy and try to deduce why we despised him so.

As we move further through, there's a whole raft of exhibits that allow you to see yourself reflected back in the cold panel of a TV screen with effects applied. This stuff, novel and entertaining back in 2003 with launch of Sony's EyeToy is looking a little bit creaky in 2014 - though at least what's on display is visually compelling. The technology powering most of these appears to be Microsoft's Kinect, which makes up for its shortcomings as a game controller by working beautifully as an art delivery device.

|

| The Treachery of Sanctuary - Chris Milk |

The undisputed highlight of this section (and maybe the whole exhibition) is Chris Milk's astonishing The Treachery of Sanctuary. In this the viewer stands in front of a series of white screens to see their silhouette. Above the screens a flock of birds spirals and loops around. In front of the first screen you see your body slowly dissolving into more birds. The second sees birds swooping down and snatching pieces of you away. The third, and most impressive, sees the subject raise their arms to find that they've been replaced by graceful feathers. As you move your arms you hear the sound of wind swooshing through them - flap your arms and you take off, flying through the air. Just watching it is fun, actually doing it is amazing.

This piece isn't breaking any new technological ground but it's a great example of an artist precisely understanding the limits of the devices they're using. This underlies much of what's on display here; it's less about marvelling at the gadgetry and more at the imagination of those using them. Perhaps the pinnacle of this comes with Dreamin' About the Future, a multimedia installation by will.i.am and Sean 'bare' Rodela.

|

| Dreamin' About the Future - will.i.am and Sean 'bare' Rodela |

Working on the principles of the 'hollow face illusion', will.i.am's polygonal face tracks you across the room. In an exhibition full of illusions that rely on mountains of mathematics and circuit boards, this one works a straightforward optical illusion; albeit one augmented with a great projection. The gigantic godlike head made me feel oddly like a worshipper of technology, staring up at some gigantic omniscient CGI god whose eyes follow me wherever I go; a subtle criticism of an increasingly interconnected, privacy free world?

I've covered but a smidge of the stuff here, but everyone should check this place out - especially if you're the curious sort who likes to fiddle with all kinds of interesting little tech toys. Other than the above be sure to check out the excellent Assemblance by Umbrellium on sublevel -2 where you can dance with light. This whole thing stinks of excellence - it's an almost embarrassingly good time.

Digital Revolution is at the Barbican Centre until 14 September 2014 - 11-8pm daily. Standard ticket £12.50.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

When I get confronted with a really good idea in fiction I feel a little thrill at the possibilities and potential stories it creates. I felt that liberation at the beginning of ‘Wreck-It Ralph’. Very quickly it establishes itself as a film that can become whatever it wants, a film that can drape itself in whatever aesthetic it chooses, a film that’s only limited by the imagination of its creators.

‘Wreck-It Ralph’ is the self-titled story of a video game bad guy. He’s the villain in a Donkey Kong-like 1980s arcade machine called ‘Fix-It Felix Jr’. Ralph’s existence consists of smashing up an apartment building, then battling Felix, the game’s hero. Felix inevitably wins, and Ralph is then unceremoniously thrown off the top of the building into a pool of mud. He’s been thrown off that building day after day for decades, and with the game’s 30th anniversary just around the corner, he’s suffering a kind of existential ennui. He isn’t an evil person, he’s just someone playing the role of a bad guy, and yet he’s ostracised by the community within the game. After being snubbed one too many times, he snaps, setting out into the wider world to prove that he can be heroic rather than just villainous.

|

| Ralph at his support group for bad guys. |

This wider world is the games arcade that Ralph’s machine is in. When the arcade is closed characters freely travel from one game to the others. Brilliantly, the world has shades of ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’, with the population consisting of ‘real’ videogame characters. When Ralph attends a ‘bad guy’s’ self help group he hangs out with M. Bison and Zangief from ‘Street Fighter’, Dr Robotnik from ‘Sonic the Hedgehog’ and Bowser from ‘Super Mario Brothers’. Seeing these characters fraternising with each other provides some of the funniest moments in the film and goes a long way to making Ralph feel like a ‘classic’ character with a familiar story. Clearly these writers and designers know their stuff, in wider shots you see more obscure characters walking by and graffiti referencing some pretty obscure gaming trivia. The relish with which these references are made underlines one important fact about the creators of this film: these people get it. 'Wreck-It Ralph' isn't a film made by people trying to appeal to gamers, it's a film made by them.

The original characters in the film fit in seamlessly with the classics, and all of them are brilliantly voiced and animated. John Reilly's gruff voice accentuates Ralph’s working class tenacity, capturing perfectly the stoical nature of a man caught in a Sisyphus-like scenario. The mirror of Ralph is the hero of his game, Felix, (Jack McBrayer). Going in I assumed that he’d be the villain of the piece; what better way to accentuate the story of a bad guy trying to be good than a good guy going bad? But, smartly, Felix is genuinely a nice guy. He’s got a down to earth, innate Southern goodness to him, sweetly exclaiming ‘Oh my lands!’ whenever he’s surprised. My favourite though was the hard as nails space marine captain Calhoun (Jane Lynch). She’s been programmed to have the most tragic back story possible, and spits a constant stream of hilariously hard-boiled dialogue like “Doomsday and Armageddon just had a baby and it... is... ugly!”

|

| Calhoun (Jane Lynch) |

The final character I found slightly less fun. That’s Vanellope, the bratty, cheeky girl outsider living on the outskirts of the ‘Sugar Rush’ world. She’s voiced by Sarah Silverman, and while I feel like a grump for saying it, she annoyed the crap out of me. Granted, this is a film for children, and she’s a good child identification character, but she's a never-ending pun machine and she drove me up the wall.

When we’re in the world of ‘Fix-It Felix Jr’ the animators brilliantly exploit capture the blocky retro-game aesthetic; everything feels like a videogame, from the cuboid bushes to the way cake splatters in pixels across the walls. But ‘Fix It Felix Jr’ is from the 80s, and our characters travel from there into more modern games: ‘Hero’s Duty’, a space marine shooter and ‘Sugar Rush’, a sweets based kart racing game. These two, particularly ‘Sugar Rush’, unfortunately feel pretty generic, environments that could have been transplanted from any 3D animated film. Once we enter the world of ‘Sugar Rush’, we stay there and it’s at this precise point that ‘Wreck-It Ralph becomes less compelling.

|

| Get used to this colour scheme, you're going to see a lot of it./ |

Nearly the whole of the ‘Sugar Rush’ sequence left a bad taste in my mouth. We switch gears from making jokes referencing videogames to jokes referencing sweets. So, our characters find themselves sinking into ‘Nesquiksand’, or pursued by angry Oreos. It’s not so much that they’re especially bad jokes, more that they have an unpleasant whiff of product placement about them. I feel like a bit of a hypocrite complaining about this, one of things I must I enjoyed in the film was seeing classic videogame characters in the background of scenes, characters which are as much corporate figures as a brand of sweets. Even so, something about product placement for Nestle doesn't sit right with me.

What’s more frustrating is that the film abandons its own compelling internal logic. Whereas the other ‘worlds’ are small and self-contained, constructed tightly around the rules of the game they’re depicting, ‘Sugar Rush’ is it’s own mini-civilisation, much of which bears little resemblance to the kart racing genre it’s supposedly parodying. It feels like you've stepped into a blander film; everything being pastel pink gets visually cloying pretty fast. I found myself wishing the film would live up to its premise and let us see some more environments, but sadly not.

It’s also here that the characters begin to come slightly unstuck. There’s a bizarrely disturbing scene where Ralph physically tortures someone for information. He picks up a talking gobstopper called Sour Bill, and licks him repeatedly until he tells him what he wants to know. Sour Bill’s reaction is sheer terror, and it’s deeply unpleasant to see our lovable protagonist torturing someone without consequence. ‘Zero Dark Thirty’ has been getting a lot of negative publicity for its torture scenes, but the torture seems slightly more sinister here. It's a worrying example of acclimatising children to the concept of the ‘good guys’ using torture to get information and at the very least the scene is a depressing symptom of a society that has grown to accept it..

But, despite the setting taking a boring and generic turn, despite the insidious corporate advertising that permeates and despite some character mis-steps, ‘Wreck-It Ralph’ remains worthwhile viewing, almost purely because the central characters are so likeable. We understand and sympathise with them, and Ralph is such a likeable, put-upon everyman that it’s impossible not to want him to succeed. ‘Wreck-It Ralph’ is a good film, one of the best non-Pixar 3D animated films yet, but unfortunately one that doesn’t quite live up to the promise of its premise.

***/*****

'Wreck-It Ralph' is on general release from February 8th

***/*****

'Wreck-It Ralph' is on general release from February 8th

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)