Thursday, May 1, 2014

'The Wind Rises' (2013) directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Thursday, May 1, 2014 by londoncitynights

Hayao Miyazaki sits at the pinnacle of animation; his only equals Walt Disney and John Lasseter. His 30 year filmography, from Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind to The Wind Rises, is beloved by children and adults across the whole world. Miyazaki poured his inspiration, his sweat and his passions into his cinema, never putting a foot wrong through his long, lauded career. And now it's coming to an end. Last year he announced that The Wind Rises was to be his final feature length film, followed by a relaxing, well-earned retirement.

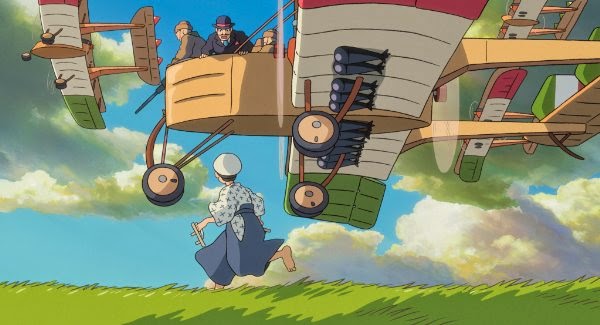

It's appropriate then that The Wind Rises summarises Miyazaki's twin obsessions; aviation and morality. This is a highly fictionalised biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, man who designed fighter planes for Japan during World War II - the crux of the film the internal conflict of a talented, passionate genius whose masterpieces tear his world apart. We follow Horikoshi from his childhood daydreams of flight, through his education and finally his professional career working for Mitsubishi as war looms menacingly over the horizon. Save for the occasional dream sequences this is much more grounded than Miyazaki's usual fare, a straightforward, sober and emotional story so deeply felt that it feels like a true passion project.

From his first films, Miyazaki has always adored flight. Practically every film he makes has an exhilarating flight scene; highlights being Nausicaä piloting her Mehve, Satsuki and Mei being carried across the night sky in My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki riding her broomstick, the hero of Porco Rosso diving into aerial combat and Chihiro riding on Haku's back through the clouds in Spirited Away. Miyazaki sees the notion of flight as freedom, or his words, "a liberation from gravity". When his characters rise above the clouds they literally see the bigger picture, the action of viewing their world from on high exposing opposing sides as part of a larger whole.

This goes hand in hand with his deeply held humanist morality. In contrast to the starkly manichean world of Disney with its clearly defined boundaries between good and evil, Miyazaki's movies never feature a true villain. There may be an antagonist, but care is taken to give them sympathetic motivations for their actions. My favourite example being Eboshi in Princess Mononoke, she's cutting down a forest in order to expand her industrial town which seems like classic environmental villainy. The twist is that Eboshi is a straightforwardly feminist defender of social outcasts, providing a refuge for former prostitutes and lepers. In Miyazaki's movies, just as in reality, good and evil are never as clear cut as they might seem.

These preoccupations reach their ultimate synthesis in the character of Jiro Horikoshi. We have to square his innate nobility, passion and quiet heroism with the fact that he's furthering the aggressive military ambitions of authoritarian imperialism. Even with the full knowledge of the misery his creations will wreak upon the world, we can't help but want him to succeed in creating beautiful flying machines - to realise his dreams even with their terrible cost.

As we progress through his life, we encounter portents of the oncoming war. A stunning sequence shows us Horikoshi navigating the Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which with its shockwaves tearing down buildings, enormous fires and earth-shaking booms is an eerie premonition of the later destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On a research trip to Nazi Germany we watch the secret police chase a man down, watching the shadows of a beating around an alley - a mysterious man (voiced the English dub by none other than Werner Herzog!) speaks darkly of inevitable, oncoming annihilation.

It's difficult not to read Jiro Horikoshi as a mirror of Miyazaki himself. Both men are expert draftsmen that transform pencil on paper into reality, both are torn between their professional careers and their personal lives, and most obviously, both dream of flying. These parallels raise an obvious question: how on earth are Horikoshi's planes and Miyazaki's animations connected? After all, one visits death and destruction upon the world, the other brings joy to millions.

The disquieting answer reveals a depressed, introspective Miyazaki - a man at the pinnacle of his profession, yet introspective, full of regrets and apparently a bit depressed. Knowing a little about Miyazaki's personal life, his estrangement from his son Goro and the amount of time he's devoted to his art at the cost of a family life helps appreciate the movie -a master film-maker questioning whether all these technical and artistic achievements were worth sacrificing his relationships for.

|

| Here you have an artist puking blood onto a canvas. Draw your own conclusions. |

To that end, The Wind Rises sits apart from the rest of Miyazaki's filmography, hitting a sober, contemplative tone that makes it difficult to recommend for younger audiences. It's essentially a low-key, intimate arthouse film, yet produced to the highest possible standards of traditional animation - a unique combination in cinema. It's beautiful from top to bottom; art design, organic sound work and considered philosophy crystallising into a film that's as precision engineered as Horikoshi's fighter planes.

It'd have been easy for Miyazaki's final film to have been a triumphant victory lap, for the master to roll out one last optimistic fairytale. For him to give us this muted, introspective, rather depressing slice of self-criticism speaks volumes as to his honesty and intelligence. The Wind Rises is a Rosetta Stone for understanding the man behind the magic, and so the perfect capstone to a glittering career.

★★★★

The Wind Rises is on general release from May 9th

Tags:

animation ,

film ,

Hayao Miyazaki ,

Japan ,

review ,

Studio Ghibli ,

The Wind Rises ,

world war 2

Get Updates

Subscribe to our e-mail newsletter to receive updates.

Related Articles

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Responses to “'The Wind Rises' (2013) directed by Hayao Miyazaki”

Post a Comment